Notes

Advertisement for the Misses Garrity studios in the 1886 Chicago Business Directory showing their 2 locations in 1886;

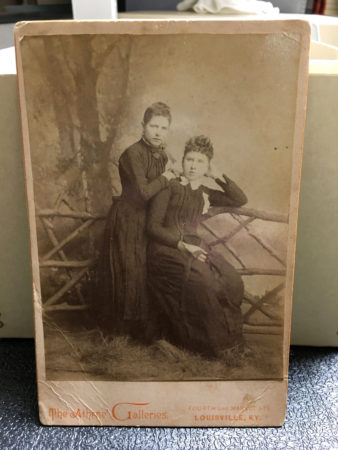

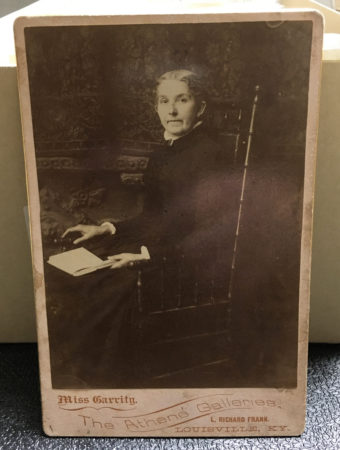

Examples of photographic works by the Sallie E. Garrity’s various “Miss Garrity” Studios (starting circa 1887)

- Cabinet Cards by Miss Garrity studio in Louisvile, Kentucky, circa 1887-1890.

Note that 2 of these show her alternate studio name, the Athené Galleries. Special thanks to Elizabeth E. Reilley from the University of Louisville Photographic Archives for providing the following images.

2. Miss Garrity opened her next studio in Chicago, running it circa 1890-1893. Here is the famous cabinet card photo of Ida B. Wells, taken by Miss Sallie E. Garrity:

![Photo of Ida Bell Wells-Barnett by Miss Garrity, Chicago. [National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution]](http://p3photographers.net/wp-content/uploads/ida.b.wells-garrity-photo-296x450.jpg)

3. Photos from the Catholic Edication Exhibit at the 1893 Chicago Worlds Fair

- Photos that have been digitized, but without any photographer attriubtion, can be viewed on this archive of the Catholic University of America.

- The descriptions of what I think are the same photos, but with the attribution to Sallie E. Garrity, are on the Notre Dame Archives website .

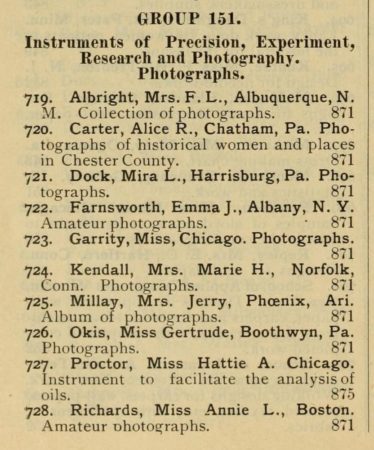

Salle E. Garrity also exhibited her own photography at the 1893 World’s Fair. Here’s a partial list of the woman who exhibited photos here:

Check it out – at the top of the list is 719. Albright, Mrs. F. L.. That’s none other than Franc Albright; see episode 48 for more on her story. Also, just a quick note that woman who exhibited as “Amateur photographs” were still extremely well-regarded in their own lifetime. For example, just above Miss Garrity is is 722. Farnsworth, Emma J. from Albany, N.Y. She was profiled in a 1901 article in the Ladies Home Journal, and Alfred Steiglitz, the “father of American photographer”, once proclaimed her as

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- Ancestry.com (census records, city directories, and more; paid account required – Visit

- Chris Culy’s blog – Visit

- Family Search website has U.S. Federal Census and more; free account required – Visit

- Geneologybank.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Newspapers.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Newspaperarchives.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Peter Palmquist database at the Yale Beinecke Library – Visit

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.

Support for this project is provided by listeners like you. Visit my website at p3photographers “dot” net for ideas on how you, too, can become a supporter of the project.

*****

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host, Lee McIntyre.

In today’s episode, I’m going to introduce you to a Chicago photographer named Sallie E. Garrity.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net.

That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers “dot” net.

*****

Hi, everybody, welcome back to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols. Today, I’m going to take you back to Chicago in the 1880s and introduce you to a woman named Sallie Evangelica Garrity, a woman who was a photographer, and very successful photographer, in both Chicago and Louisville, Kentucky, in the 1880s and early 1890s.

In 1880 she’s living with her parents, and several of her siblings in Chicago. Sallie – at the age of 18 – is already working in a photo gallery. Sallie, ir should be noted, started life as a woman named “Sarah”. But “Sarah” turns into “Sallie” pretty quickly. So I’m going to refer to her as Sallie Garrity throughout this podcast.

So Sallie is working in the photo gallery in 1880. Because of the availability or lack thereof of directories that have been scanned for Chicago, in the 1880s we’re going to have to fast forward to 1885 when we next find Sallie Garrity working as a photographer, running her own studio with her sister, Mary Garrity, who is two years older. NoW in 1880 (in that census record) Mary Garrity did not have a profession noted. But some time between 1880 and 1885, Mary Garrity has been taken into the photography business by her sister, and they’re running a studio called the Misses Garrity studio. Misses is spelled M I S S E S – i.e., multiple “Miss Garritys” are running the Misses Garrity studio together. Interestingly, their slightly younger brother Thomas is working for them as a photographer.

Again, it’s hard to say exactly what happened between 1880 when Sallie Garrity was working for some other photographer’s studio, and 1885, when we find her running the studio with her sister. We’ll come back to what might have been happening then in a little bit.

But by 1885, the sisters are running the studio in Chicago. It turns out, based on an ad that’s in a business directory for Chicago in 1886, that we find out that the two sisters were actually running two branches of that Misses Garrity studio, one in Chicago, and one in Louisville, Kentucky, a few hundred miles away.

So, by 1886 they’re running these two studios and making a success of it.

But then in 1886, life changes for the Misses Garrity.

First, Mary Garrity meets and marries a man named Thomas J. Webb, who’s a businessman who eventually becomes a very successful coffee and tea merchant in Chicago. At the moment when Mary Garrity marries Thomas Webb, she seems to give up photography; there’s no evidence that Mary Garrity {Webb] ever again works as a photographer.

Around that time, and maybe it’s because Mary got married (?), Sallie gives up the Chicago studio and moves to Louisville, Kentucky, and focuses on that studio.

She rebrands that studio — because Mary’s no longer working with her — so the studio in Louisville is rebranded as the “Miss Garrity” studio. That will continue to be Sallie Garrity’s brand for most of the rest of her career.

When we find her in Louisville, in a 1887, it’s not just Sallie who’s moved to Louisville, Kentucky, but the whole rest of her family has moved there as well. And Sallie seems to be the breadwinner in the family. Her father apparently has died by this time; Sallie is supporting her mother, her brother Thomas (who’s working for her), and her younger brothers Aloysius and John, who will eventually go to work for her but are not at that moment.

But interestingly, in addition to the photography studio in 1887, she and her mother try to set up a new college, called the Kentucky College of Music and Art. For a couple of years is Sallie’s in the papers trying to raise money, and her mother is trying to raise money as well, trying to get some financing for this college.

They get some instructors [to sign on] but then Sallie has a very big falling-out With one of the instructors they initial hire – a woman named Madame Octavia Hensel, who is described as the instructor of vocal culture.

But the main problem is that the money isn’t there. And so, college is ultimately forced to close in 1890, after just a couple of years. By the end, Sallie’s youngest brother, John, had actually taken over what had been described as Sallie’s responsibilities for the college, probably because Sallie then was able to then focus again on her photography studio.

But in that period where she is attempting to raise the money for the college, she rebrands the studio briefly to something called the Athené gallery, spelled a t h e n e with an accent, so I’m not quite sure how to pronounce it. There are some examples of work from that Athené studio that have both Miss Garrity’s name and also the name of a man, L. Richard Frank. L. Richard Frank apparently was hired by Miss Garrity to be the photographer at the studio during this period of 1888-89, the point at which Miss Garrity was distracted by all the college issues.

That connection to the Athené gallery – the having this other photographic operator working for Miss Garrity – was something that was revealed by the collection at the University of Louisville. I want to thank Elizabeth E. Riley, who is the curator of the Photographic Archives at the University of Louisville for supplying these examples from Miss Garrity’s gallery, because it’s really interesting to see this alternate name for that studio. In the directories at the time, the photography gallery is always just listed as Miss Garrity’s name, it’s never listed as that Athené gallery name.

So, bu 1890 the college has been forced to close, and Sallie Garrity throws herself back into photography full force. She winds up with a very nice sort of “puff piece” profile in something called the Photographic Times that appears circa March, early March of 1890. She’s portrayed as a successful 27 year old woman photographer who has been independently building her business; she’s netting $10,000 a year!

She is portrayed in this article as a woman who learned photography by working for other people, and that sort of checks with that 1880 census that we see where she’s working for another photography gallery.

But in this article, her “origin story” as a photographer, the way she portrays it, is that when she first opened her own studio, she hired a male camera operator to be the photographer, because she had only learned the business of running a photography studio, not the actual mechanics of making a photograph.

This is what she claims in this 1890 profile.

Let me just read you a little bit about what she says about all this. Again, I’m quoting from this 1890 profile. It says …

she engaged an artist and set up a studio on the north side of the city of Chicago. – i.e. when she first opened a gallery, after she worked for other people for a few years.

It goes on to say …

But her assistant was too wasteful to suit her practical business ideas. And she remonstrated with him, it did not suit his dignity to take directions from a woman. And he told her he wouldn’t stay any longer. She replied that she didn’t want him any longer, then you better go and be quick about it.

The story goes on to say there were….

people were waiting to be posed, negatives were waiting to be developed, pictures were waiting to be finished. And not one of these things had the young woman ever done, for she had attended only to the business side of the establishment. Nevertheless, she pluckily bundle her artist off, rolled up her sleeves, and went to work as calmly as if she had known all about it for the last 50 years.

So the story goes on with a few more details. But basically what it’s saying is that when she first opened her studio, she hired a man to work with her. He knew how to take a picture, they had falling out, and she had to overnight turn herself into a photographer.

Which is a great story. I want to believe that it’s true.

However, knowing that she did work with her sister in 1885 and 1886, and that’s not mentioned anywhere in this profile, Iie got to wonder. Was this supposed to be something that was describing a period before the Misses Garrity gallery in Chicago?

It is really too bad that the directories 1882 and 1885 are not available online. At some point, I really want to follow up with someone in the Chicago archives and try to track down a little bit more about whether there’s any possibility that this story that Miss Garrity tells in 1890 was actually true about how she turned herself into a photographer overnight.

Alright, so we’ve had the phase of the Misses Garrity gallery in Chicago – that’s phase 1 of Miss Garitty’s career.

Then we had the phase in Louisville from 1887 to 1890. During that period in Louisville, she opened up a second branch in Bowling Green, Kentucky as well. That branch was run by her brother Thomas, who of course had been working for her for years.

Things seemed to going really well at the beginning of 1890. But unfortunately, at the end of March 1890, the Louisville reservoir bursts and floods Louisville, and the Miss Garrity gallery is completely flooded.

Sallie does manage to resurrect it and clean it out and build it back up, thnough.

At that point, she may or may not still have the Bowling Green branch run by her brother Thomas. There are no directories [online] from Bowling Green from that period. And there’s some other complications that happened around that time with Thomas. So it’s possible the Bowling gGeen studio branch actually got closed.

But as I said she had rebuilt her Louisville studio after the flood.

But then in December 1890, there’s a notice in the paper that she’s actually selling it to Mrs L. Richardson; Miss Garrity is then moving to Chicago. S

So that’s then going to be the third phase of her photography career – take 2 in Chicago is moving back there and setting up a new Miss Garrity gallery.

There are a couple of reasons that she might have chosen to go back to Chicago around the early 1890s. One is that back when she moved to Louisville in 1887, there was a notice in the paper that Miss Garrity had been the first woman to sign up to display her art – i.e. her photographs – in the Women’s Pavilion in the upcoming 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. That was back in 1887.

But of course in 1890 the Expo is now starting to come closer, and so she’s going to have to go and start arranging for that.

She’s also taking on assignments to take pictures of some of the other exhibits at the World’s Fair, too. For example, Miss Garrity took pictures of something called the Catholic Education Exhibit, at the Columbian Exposition, the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. There are photographs of that Catholic Education Exhibit that are in the Catholic University Archives. Those photos that are scanned and available online in the Catholic University Archives, but none of those are actually attributed to Sallie Garrity; there’s no photographer attribution at all.

However, the Notre Dame archives has online a whole guide to their photographs from that Catholic education exhibit at the World’s Fair of 1893. And in their guide to the photographs, they attribute all of those photographs to miss Sallie E. Garrity. I think the guide to the Notre Dome archive photos matches up with the photos that are online at the Catholic University. I’ll put links to both of them and you can judge for yourself.

But I think it’s interesting to see Sallie E. Garrity’s work in the types of photos she took for this exhibit. It’s also interesting she was getting that kind of commission; by being based in Chicago, she would be well-positioned as Chicago photographer who would be contacted to take pictures at the 1893 World’s Fair.

But of course, she is exhibiting her own work as well in the Women’s Pavilion. And just to point out, I’ve mentioned the 1893 World’s Fair on the podcast before. If you might recall that Franc Albright (Episode 48), Mrs Albright, from New Mexico was very instrumental in setting up the New Mexican pavilion at the World’s Fair. But in addition, she exhibited her own photography at the Women’s Pavilion; her name is listed in the program right next to Sallie Gary’s name for having displayed their photographs as professional photographers. The display of women’s photography [at the World’s Fair in 1893] included both professionals and amateur photographers.

Another woman who is in Chicago in 1893 was a young black journalist and civil rights activist named Ida B. Wells. Wells ran a successful newspaper in Memphis, Tennessee in the 1880s, but 1892 her offices were attacked by an angry white mob protesting writing she had done against lynchings in the south. Ida b. Wells was away on a trip to New York City at that time and, fortunately, she was out of harm’s way when the mob attacked. But her offices were destroyed and she was unable to return to Memphis because of the danger.

So she wound up traveling the country and continuing her crusade for better treatment for blacks.

According to the online encyclopedia of Chicago, in 1893, Ida B wWlls traveled to Chicago to protest the exclusion of African Americans from the exhibits at the World’s Fair. She and Frederick Douglass actually co-authored a pamphlet called The Reason why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian exhibition. They distributed that pamphlet at the fair.

I bring this up because one of the most famous early photos of Ida B. Wells was taken at the Chicago studio of one Miss Garrity. The original cabinet card photo is owned by the Smithsonian Museum’ss National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. And they have a copy of that online which I’ll share in the Episode Notes for today.

Now, we can only speculate what brought Miss wWlls into Miss Garrity’s gallery there in Chicago.

As a side note, you might recall that Frederick Douglass actually had an interest in photography, and he had traveled a generation earlier to Chicago to have his photo taken by the celebrated Chicago female photographer of that era, one Lydia cadwell (Episode 58).

Anyway, as it turns out, the photo of Miss Ida B wells by Miss Garrity is referenced and used in countless write ups when you look across the internet and in books about Ida B. W Well’s life. The Smithsonian correctly identifies that the “Miss Garrity” – the photographer for that photo – was Miss Sallie Garrity. But I have seen it misidentified as “Mary Garrity” as that photographer. But of course we now know that that’s false since Mary Garrity gave up photography when she got married in 1886.

Anyway, I’m hoping at some point to run across some more information about how Ida B. Wells happened to get her photo taken by Miss Garrity in Chicago, circa 1893. If anyone out there has any information to point me towards, please do get in touch.

But in any case, I thought it was just interesting to find this connection between Miss Garrity; Miss Garrity’s work is actually collected and she’s therefore somewhat celebrated as a photographer because of the person in the photo she took.

And we have one more bit of news from 1893 regarding Sallie Garrity and a connection to the 1893 Colombian exhibition.

In the Chicago daily news on December 16 1893. There’s the following notice in the paper,

Miss Garrity to wed: Chicago’s well known Lady Photographer Marries an Ex-Consul.

William Elmendorf Rothery, consul for Liberia for the past 10 years of Philadelphia and recently the World’s Fair Commissioner for the same country will be married this evening at the residence of Archbishop Feehan. The bride will be Miss Sallie Evanngelica Garrity, the photographer at Jackson Street at Wabash Avenue. After a week’s trip through the east, the couple will settle in Chicago permanently.

However, unlike what it says in that notice, the couple does not seem to settle down in Chicago. In fact, Miss Garrity – Mrs Rothery – closes her studio and seems to give up photography entirely. The Rotherys move west, where they become newspaper and magazine publishers. Sallie Rothery also writes newspaper and magazine articles.

Now William and Sallie Rothery apparently had a rather interesting marriage relationship, because we see them in the directories sometimes together, sometimes apart, sometimes living apart in the same town, or sometimes living in different states. Mostly Sallie is based in Los Angeles, although at one point she does wind up living in San Francisco. William, on the other hand, turns up all up and down the west coast.

In the 1900 census it seems that was a period when they were living together. They were both in LA and Sallie’s niece, the 19 year old Florence Keefe (who was the daughter of her elder sister, Catherine) is actually living with them.

By 1906, though, the marriage for the Rotherys is over. And Sallie, who’s at that point living in LA with her sister Catherine, sues for divorce from William Rothery. He’s up in Portland at this point.

A notice appears in the LA Times on August 4 1906 that, “Sallie Rothery obtained a decree from William E. Rothery on the grounds of failure to provide and dissipation”, among otherthings.

In August of 1906, at the time of the divorce, Sallie is only in her mid 40s. She’s already had several successful careers to this point, including, originally, she was a photographer, and then later she is a newspaper publisher, a magazine publisher and a writer.

She’s listed in the 1907 L.A. directory but there’s no occupation listed for her, so there’s no clue as to what she’s planning to do next.

But then … on June 17 1907, less than a year after her divorce from William Rothery, Sallie E. Garrity Rothery, age 45, is dead.

Her death is attributed to dropsy, which today we would call edema.

She dies in Ocean Park, California at the home of her sister, Catherine Keefe.

I have to say, no matter how many stories my husband and I dive into to track down the lives of these early women photographers, it’s always a shock to run across an unexpectedly early ending to the story when someone dies so young. Very sad.

… So, that’s the life story of Miss Sallie E. Garrity, a Chicago photographer who built a successful photography practice with multiple studio branches both in Chicago and places in Kentucky over a 10 or more year period.

And she’s an example of a woman photographer who partnered with a sister early on in the Misses Garrity studios that were in both Chicago and Louisville.

And then, as Miss Garrity, she continued to build her studio and her reputation as a skilled photographer, all on her own.

*****

In the episode notes today, I’ll include images by Miss Garrity, including some from the University of Louisville archives. Again, I want to thank Elizabeth Riley for sharing those examples and allowing me to share them here with the podcast.

I’ll also put some links to that archive at Notre Dame and also at the Catholic University, which have the information about and digital copies of Sallie Garrity’s pictures of the Catholic education exhibit.

As always, these materials will be available on the website at p3photographers.net.

If you have any questions or have any information about Sallie Garrity’s work that you have from any other archive or that you’ve run across on your own, please do drop me a line at podcast “at” p3 photographers “dot” net.

Also, I do put information on the Facebook page for the podcast, which facebook.com/p3photographers. This month, look for more information about a new feature I’m hoping to start which will have some more information about the “side stories” that I wind up uncovering when we’re looking for information about the photographers. Chris and I are both fascinated by the side stories, and I always want to share them, but I’ve decided that I will take them out of the main story on a photographer if she isn’t directly involved with the story.

But, I do want to share them. So look for more information about that later this month.

I haven’t quite figured out how I’m going to write it all up yet.

But I have to say, Sallie Garrity is indirectly connected to a lot of intriguing side stories. But a lot of the ones about her husband, for example, actually start right after her death.

Anyway, look for more information about this new “side stories” feature on the Facebook page (facebook/p3photographers). I’ll also put some links on the regular website, too, whenever I post that information, at p3photographers.net.

But in any case, that’s it for today’s episode.

I hope you enjoyed this introduction to yet another talented early women photographer from Chicago. Special thanks to my husband, Chris, for doing a lot of extra research to track down some of the details about Sallie Garrity, which were a little bit harder than normal to track down due to variation in spelling and – as I mentioned – all the missing directories. Well, missing from the standpoint that they are just not available online.

In any case, thanks for stopping by today!

Until next time, I’m Lee and this is Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.