Notes

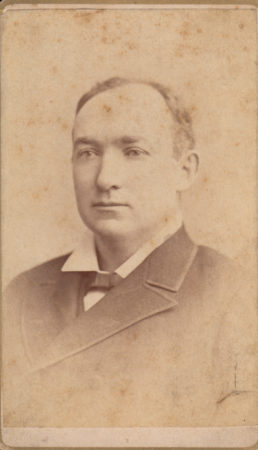

Here’s the CDV that Chris and I found that started our quest for information about Lydia J. Cadwell:

As discussed in the podcast episode, Mrs. Cadwell was a talented inventor, holding at least 5 u.S. patents as well as 2 Canadian patents. Here’s the first page of her general patent for “desiccating substances” , granted in 1881:

Regarding her marble mining venture, you can see a photo of the green Riccolite marble on this website.

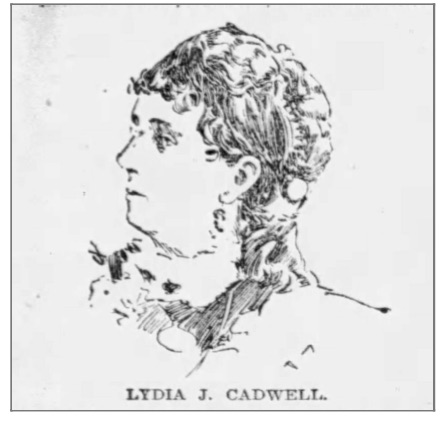

Finally, this sketch appears as part of the long obituary about Lydia Cadwell in the Chicago Tribune, Jan 1896:

The full text of her obituary in the Chicago Tribune is available here (on newspapers.com – requires free trial account or paid subscription

Here’s a link to one of the photos of Frederick Douglas taken that day in January 1875 by Lydia J. Cadwell of the Gentile Gallery in Chicago:

The book Picturing Frederick Douglass by John Stauffer has 3 photos by Lydia J. Cadwell reproduced in it.

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- Ancestry.com (census records, city directories, and more; paid account required – Visit

- Chris Culy’s blog – Visit

- Family Search website has U.S. Federal Census and more; free account required – Visit

- Geneologybank.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Newspapers.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Newspaperarchives.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Peter Palmquist database at the Yale Beinecke Library – Visit

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.

Support for this project is provided by listeners like you. Visit my website at p3photographers “dot” net for ideas on how you, too, can become a supporter of the project.

*****

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host, Lee McIntyre.

In today’s episode, we meet a woman of many talents, the phenomenal Lydia J. Cadwell.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net.

That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers “dot” net.

*****

Hi everybody. Welcome back to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.

Hi, everybody! Welcome back to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols. As we kick off season six today, I want to introduce you to Lydia J Cadwell, an extraordinary woman from the 1800s who rightfully could be called a type of Renaissance woman. Not only was she a successful photographer in Chicago, in the 1870s, she was also an influential patron of the arts, a writer, a poet, and also an inventor holding at least five patents for inventions that had nothing to do with art or photography.

Her story intertwines, not only with a U.S. president, but also with an American social reformer, writer, writer, abolitionist and statesman who was one of the most photographed men in the mid 1800s and who famously only had one photo taken by a woman: and that woman was Lydia J Cadwell.

Now, I think I may have mentioned it before, but I always find it oddly exciting when I run across a really informative obituary about one of these women. So imagine how excited I was when I discovered that when Lydia J Cadwell died in January of 1896, the Chicago Tribune published almost a full column obituary about her, profiling her life and her accomplishments.

As Chris and I started to piece together other bits of information from other records online, as well as other contemporary news articles, well, it turned out that some of the details about her personal life in that obituary were a little bit more complicated than you might think from reading the obituary.

But amazingly all of the incredible accomplishments of Lydia Cadwell that are listed in her obituary are actually true. And … there’s even more to her accomplishments than the obituary lists.

So without further ado, let’s just dive into the story of Lydia J Cadwell, who was a woman who really packed a lot of living into her 59 years.

Lydia J. Doty was born on February 3rd, 1837. She was the daughter of Henry Doty who was actually a descendant of the family of John Quincy Adams, one of the U.S. Presidents. According to that 1896 obituary for Lydia, she had worn, until her death, a ring that that had been presented to her by John Quincy Adams when she was a little girl. The story was that he received it from an Italian Prince.

I looked it up, and John Quincy Adams died in 1843, and Lydia was born in 1837.

So it is possible that, John Quincy Adams met little Lydia and gave her that ring. And it is possible that she actually did wear it for the rest of her life.

Unfortunately, there’s no trace I could find online of any story about John Quincy Adams receiving a ring from an Italian Prince. But, that story is there in the obituary — and it is a really cute little story.

But I want to leave Lydia after she gets that ring, and fast forward up to 1870. Lydia is at this point living in Grand Rapids, Michigan with her teenage daughter, Ella.

Now I’m getting this information from the 1870 census where Lydia is listed as a 31-year-old widow living with her 15-year-old daughter, as I said, Ella, and also their 17-year-old “domestic servant”, a woman named Betsy Blank.

Lydia is listed in 1870 as “keeping house”. In other words, she doesn’t have an outside occupation that’s listed. And her age there is a little bit off. She should have been more like 34, not 31, but that really isn’t that surprising because we run across a lot of people who seem to become miraculously a little bit younger in their census listings.

Where I really want to pick up Lydia’s story is a little bit later in the 1870s. By that point, she’s living in Chicago and she’s working as a photographer.

Unfortunately, the Chicago directories that are available online have some gaps in that period of the early 1870s. So I can’t pinpoint exactly when Lydia started her career in photography in Chicago.

And Chris and I haven’t really been able to figure out if she actually did any photography prior to going to Chicago in the early 1870s.

But definitely Lydia is working for a photographer in Chicago named Charles Gentile, and she’s working at his studio, which is named the Gentile studio. That’s in Chicago, I said, in the early 1870s.

Later on in the 1870s, Lydia will actually become the co owner of that studio with Mr. Gentile. And then she takes it over completely by 1878.

But even before 1878, Lydia Jake Cadwell has already built a reputation for the quality of her work. She’s particularly sought after by people who come to see her — people who want to have their portraits taken by her.

That’s the case in January of 1875. On January 5th, 1875, a rather famous man come sto call, a man named Fredrick Douglass, who was that orator, statesman, and abolitionist that I mentioned. Well, he comes to Chicago (he’s going to give a talk there). And according to his biographies, he detours over to the Gentile studio to have his photo taken by Mrs. Cadwell, because he had heard of her reputation and her skill.

There are at least three photos that were taken that day at the Gentile Studio by Lydia Cadwell. And they are reproduced in biographies written in the last few years about Frederick Douglas. I’ll put some links in the episode notes, so you can find them.

Now the Tilley’s duty was clearly very popular there in Chicago, not just because mrs. Cadwell’s famous, but they have a lot of articles in the paper promoting stuff that they’ve got going on.

In 1876, the year after Frederick Douglas was there, there’s a big article in the Chicago Tribune that says that the Gentile gallery had on display wat was termed a massive 72 inch by 44 inch photo of the First Regiment. That First Regiment of soldiers, according to the article, is represented after the breaking of the ranks after the last formal review of the soldiers, in South park in Chicago.

Let me just read you a little bit of that story to get a sense of what this was all about.

Again, this is from an article Chicago Tribune on June 4th, 1876. So the description of the photo is as follows,

This mammoth picture, which covers an area of 72 by 44 inches is a photographic view of the first regiment and represents the scene of the breaking of the ranks at the last review on the South Park.

There are over 400 figures, grouped in most lifelike postures in the center; foreground it’s the officers

(and it names all the generals on either side) …

and to the rear almost as far as the eye can reach are the men and noncommissioned officers of the regiment, picturesquely grouped, while stacks of arms and piles of drums, and the two regimental flags — beautifully draped — relieve the scene in a very artistic manner.

Each figure is a separate photograph and no two have the same pose. These photographs have been graduated in size so as to thoroughly meet the laws of perspective, and all have been so mounted as to produce a perfectly harmonized whole.

So in other words, this giant photograph is actually a giant composite of multiple photographs, at least more than 400, since there are more than 400 people represented all “carefully placed” so as to look like they were actually taken as a snapshot of people on the field. But in fact, it’s actually composed, and according to the newspaper article, the person who composed that scene was actually Mrs. L J Cadwell, the “cashier” of the gallery.

Now it terms her the “cashier” of the gallery, but we know from the directories and from other articles that she actually was also a photographer at the gallery. So this is a very special photo that the Gentile gallery really promotes as being something special and something that people should come to see in their gallery.

It’s really kind of intriguing that she was doing this kind of composite work in addition to their other kinds of cabinet photos and that kind of things in the 1870s, because we also did see this with Hannah Maynard (a woman who was in Victoria, British Columbia, who I profiled on a previous episode). Well, Hannah Maynard was doing composite photography, but actually a little bit later than the 1870s; Maynard was doing it, I believe in the 1880w.

So anyway, so Mrs. Cadwell is very, very popular and very well known as a really good photographer and artist in terms of creating this artistic composite scene of figures and drums, et cetera.

Now, as I said, at this point, Lydia is partnered with Gentile, but she eventually buys him out. And by 1877, we find her in the directories as the sole proprietor of the stuido that’s now billed as “Gentile & Co”.

And then, in 1878, Lydia is not only running the Gentile photographic studio, but she’s also opened an art gallery called the Lydian art gallery. The Lydian art gallery showcases artists from all different kinds of media. I mean, not just the photographers, but painters and sculptors, et cetera. She is organizing exhibitions by these artists and sponsoring their work.

These art exhibitions by Mrs. Cadwell become quite legendary there in Chicago. Really a high society event. She has a very fancy advertising and invitations that get sent out. According to her obituary, at some of these parties she would host a 1000 people.

I’m not sure that I can verify the numbers of people who are at these openings, but I can verify in the newspaper articles that these were just the pinnacle of the art world there in Chicago in the 1870s. And by the early 1880s, that Gentile photography studio, plus the Lydian art gallery (which are actually co located in the same building) — well, they are still going strong. I mean, mrs. Coldwell is really well known and influential in art circles in Chicago.

And eventually she’s even credited as being one of the founders of the Chicago rt Institute.

So she’s very powerful and very much a force within the art world in Chicago.

But even though she’s so involved with photography and art, that isn’t her own area of involvement during this period, she gets involved with other creative endeavors, not just visual arts, but she also does a lot of writing, particularly poems.

Two of her poems actually become quite famous. One is a tribute to a bouquet of flowers that she received when she was about to embark on a European tour. And then one of her other famous poems was actually one that was a tribute to a famous singer who loved that bouquet poem so much that she commissioned to have it set to music.

There’s also this other curious mention of her poetry.

If I take us back to March of 1875, remember that in January of 1875 is when she photographs of Frederick Douglass. In March of that year, there’s an article in the paper that she has been made an honorary member of the National Egg and Butter Association.

Now this was a time when the National Egg and Butter Association did not permit women to be members. So the fact that a woman has just been made an honorary member is actually quite a big deal [in 1875]. The following year, The coverage of that year’s annual meeting says that Mrs. Cadwell reads an original poem at the meeting called “My Past and Present.””

And according to the notice in the paper, her reading of her poem was met with “such rapturous applause that the lady was obliged to respond with a second original poem before she was allowed to return to her seat.”

Alright. So she’s really quite talented and well-regarded as a poet; this is at the same time she’s well-regarded and famous for her photography.

And of course it’s just around the time when she’s thinking of getting her Art Gallery going. Lydia Cadwell has a lot going on when it comes to creative endeavors.

But if I go back to the 1875 article, when she’s made an honorary member of the Butter and Egg society … well, I don’t know why she was made the honorary member.

But I can tell you that it was around that time she files an application for a patent on a process to desiccate or dehydrate eggs. Now she actually was awarded that patent in the early 1880s.

And it turns out that’s just one of many patents that Lydia received, not just in the U S but in Canada as well. All of her patents involve some sort of desiccating or dehydrating things: eggs, slops, grain.

I think Chris located the 5 US patents online, and there are two more that we’ve found in Canada which were from the period of the 1870s all the way up through the 1880s.

One of those patents actually led to the creation of a wheat drying machine. And that was such a successful and popular machine that some rather “unscrupulous people” tried to steal the patent and then the machine patent from her. But according to her obituary, it says that she was on to their tricks, and she headed them off by getting a controlling stock in a company that made that machine. Good for her!

And really, if that wasn’t enough of another sideline … at some point, she becomes the owner of land in New Mexico that becomes famous because they find what’s called Riccolite marble. This green marble continues to be sold and continues to be quite popular even today.

But back in the late 1800s, it was apparently very popular and very profitable.

Again, I want to emphasize that all of these things are in addition to her success in the art world, both with photography and her art gallery.

She was really quite a woman of many talents. I mean, so we have evidence that she was a poet, inventor, art patron. Among the talented women that we’ve run across, there are very few that have all of these things combined. But we find them all in Lydia J Cadwell. Chris and I have been able to confirm that all of these facts are true.

So, she’s really quite striking.

But you may have noticed that I haven’t really talked much about her personal life other than the fact that she was married at some point, obviously. And then in 1870, she’s listed as widowed with a teenage daughter. Okay. So this is where it gets a little bit tricky …

Lydia J. Doty grows up in New York state. And at some point she meets and marries a man named George w Cadwell. Now, according to her 1896 obituary tragedy struck right after the wedding, and she was left a widow at the age of 19. She then moved to grand Rapids, Michigan, where she lived for several years after she was widowed.

Again, this is according to her obituary.

Nowm she was born in 1837. So if she had been widowed around at the age of 19, that would mean that George Cadwell would have died around 1856.

And that is a very tragic story; it’s certainly very remarkable and compelling.

The problem is … it’s not at all true! Because George doesn’t die until 1885, and he’s actually been married again (and actually widowed) [Note: the audio incorrectly says George was married to his second wife at the time of his death]

So the real story is that Lydia files for divorce for George in 1871.

So she’s not widowed at the age of 19.

We in fact, find them living together in Oneida New York in the 1860 census, along with their daughter, Ella who’s 4.

Now, as I mentioned earlier in 1870 census, Lydia is living in Grand Rapids with her daughter, Ella, and George is no longer on the scene. [But he’s not dead.]

But Lydia lists herself as a widow in 1870. So it turns out that when she says she’s a “widow”, it’s what Chris likes to call a “widow?! because of course she’s actually not widowed. Now George and Lydia do get divorced and she does file for divorce any 71, but Ella continues to live with Lydia until George remarries.

And at that point it seems like Ella goes to live with her father. After that 1870 census, when Ella is living living with Lydia, we don’t actually find any other mention of Ella ever living with Lydia in Chicago. And in fact, in Lydia’s obituary in 1896, there’s no mention that Lydia has a daughter, even though Ella survives into the 20th century.

So it’s really kind of intriguing that at some point, whether it was when she became a photographer, or maybe it was when Ella moved out and moved with in with her father, that Lydia created a narrative for herself that was a little bit different from what reality was.

And, you know, I can respect that she wanted to reinvent herself. But it really is intriguing wanting to know, you know, what happened there and what was the story?

I mean, Ella, unfortunately is always described as an invalid. And so she needed a lot of care and always needed to have a companion. And when her father dies, i.e. when George Cadwell dies in 1885, he actually is pretty prominent where he’s living and his estate is detailed in the press. And it turns out that he leaves his entire fortune to his daughter, not to his son from his second marriage.

So interesting, intriguing … but that’s a complete side story because we have digressed away from Lydia.

So what I really want to talk about of course is Lydia. And that’s why it’s really hard to piece together elements of her personal story. But her professional story and all of her accomplishments, what is fascinating is that that can be confirmed, that she was involved with all these different things and had such success in so many of them.

OK.

So when last we saw Lydia, she was operating the Lydian gallery and the Gentile studio for photography. We’re in Chicago in 1882, where she just gotten at least one patent and life is going well.

And that is when tragedy does strike. On December 28th, 1882, on a day that was described as a cold winter day with ice on the sidewalks, Lydia J Cadwell slips and falls and hits her head. According to newspaper articles that are written in her lifetime, she is gravely injured by that, and she’s left with what is usually described in the papers as “an abscess on the brain.” She loses her hearing, and it is said because of that, she actually gives up her art: she sells her studio and her gallery.

Now that’s 1883, 1884 around that time.

And according to obituary, tt’s at that time that she turns to the scientific inventions But in fact, we know that the dates on her patents, and on that egg machine definitely, all indicate that she was already doing that prior to her fall in 1882.

So yes, she really was a woman who could coordinate many different interests and do them all well until her fall. And then, you know, she withdraws from the art world, but she has still has a lot of success and makes money apparently with those patents and the inventions, as well as that marble company, etc.

But apparently the fall really did leave her severely injured and she never fully recovered from those injuries. And so, in January of 1896, unfortunately she passes away, and they blame her death on the injuries she suffered in 1882.

She was only 59 years and she left quite a large estate, but she died intestate. So there are actually articles in the paper about how people are trying to do to shore up the estate, and about who is applying to become executor, etc. There were no bequests to any family members – and as I said, her daughter is never mentioned in any of the articles.

So it is a rather tragic end in terms of that fall and the fact that she gave up the photography and the arts, or at least the art gallery. But during her remaining years, she continued to be a popular figure and still involved in the art world, at least on the sidelines.

She is celebrated in Chicago up until 1896 when she passes away. As I said, her death rates a rather large obituary with a big headline.

But it was really intriging to try to figure out exactly what was going on with Lydia J. Cadwell. How did she become a photographer? How did she become an inventor? How did she become interested in inventing a machine to dehydrate eggs? I really would love to know a lot more about her story. And maybe someday we’ll run across some more information about her.

But, for the moment, I think I just want to celebrate this woman that we ran across by buying a small CDV. The photo had the name of the Gentile studio and the Lydian Art Gallery on the back, along with the name of the photographer who ran both of those things: the fabulous woman named Lydia J Cadwell.

*****

There are a lot of different kinds of materials to share with you about Lydia J Cadwell and you’ll find links and other photos, et cetera, on the website as usual, which at p3photographers “dot” net. Remember that’s letter “p” number “3”””, photographers “dot” net. If you have any questions or just want to drop me a line, write to podcast at p3photographers “dot” net.

Remember you can also contact me through the Photographs, Pistols & Parasols on Facebook page at facebook.com/p3photographers.

I really want to thank everyone who contacted me over the last couple of months with questions and suggestions. Really. I have many intriguing paths to explore that have been opened up through your messages.

And I’ll be addressing some of your questions and providing some more information about some of the women you’ve asked; look for that over the next few months here on the podcast.

But in the meantime, I thought Lydia J Cadwell would be a great woman to kick off Season 6. For the resst of this season, I’m going to be profiling various women who were in Chicago or New York, including some who were in both Chicago and New York; as well as women over the West Coast.

So we’ll be discovering a lot of different women over the next few months who, as always, will all be talented early women photographers, artisan photographers all.

Also one final note. My husband, Chris, who as listeners of the podcast know, works with me on this project.

He’s actually started his own blog where he sometimes talks about some of these early women photographers. His blog address is blog dot chrisculy dot net. That’s B L O G “dot” C H R I S C U L Y “dot” net. At the moment, he’s in the middle of a 5-part series that describes the kind of deep dive that he and I do when we’re trying to find information about women like Lydia Cadwell; he’s describing how we look at newspapers and ancestry.com and all kinds of other materials.

He has a fun way of explaining all the different twists and turns one of our deep dives can take. So I really encourage you to check it out.

But that’s it for today. Thanks as always for stopping by!

Until next time, I’m Lee, and this is Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.

1 thought on “58 – In a class all her own”

Comments are closed.