Notes

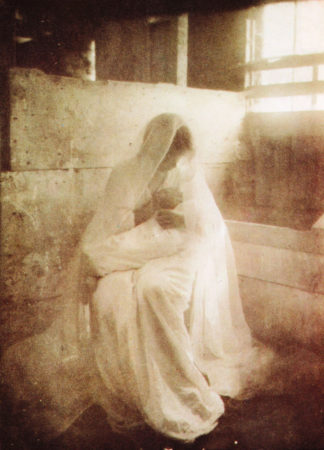

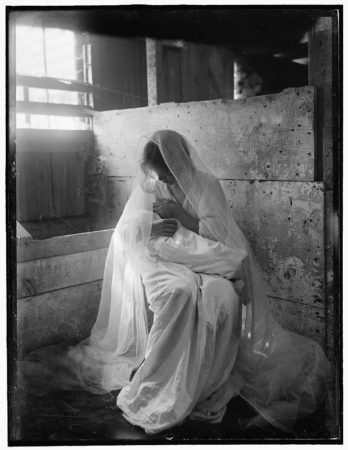

The first image above is Gertrude Käsebier’s pictorialist image The Manager, a photo that sold for the then-unheard of sum of $100 in 1899. The second image is a scan from the Library of Congress of what is labelled an “experimental negative” version.

Comparing the two images reveals some of the pictorial darkroom “magic” done by Käsebier to create The Manger. Note the softness of the focus, the brightness of the whites, and the addition of shadows around the edges to create almost a vignette effect. All the changes evoke a dreamy, romanticized mood this is the hallmark of a Pictorialist style work.

This is just one example of Gertrude Käsebier’s marvelous photography. More aspects of her remarkable life and career will be discussed on future episodes of the Photographs, Pistols & Parasols podcast.

In the meantime, be sure to check out some material I’ve put up on the board for this episode on Pinterest.

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- Gertrude Käsebier: The Photographer and Her Photographs, by Barbara L. Michaels – Buy

- Gertrude Käsebier: The Complexity of Light and Shade, by Stephen Petersen and Janis A. Tomlinson, Editors – Buy

- Ambassadors of Progress: American Women Photographers in Paris, 1900-1901, by Bronwyn Griffith (Editor) – Buy

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host Lee McIntyre.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers.net.

In today’s episode I want to introduce you to a woman named Gertrude Käsebier. She’s one of a group of photographers that I tend to refer to as an informal canon of women photographers whose careers are somewhat well-known in photo history circles. Käsebier ‘s full career was extraordinary, and I’ll be including more stories about her in future podcasts.

Today, though, I want to tell you about her involvement with what I call the $100 photo.

It’s 1899, and a photograph has just sold for $100.

Now that might not seem like a lot of money in today’s dollars, but in 1899, well, that was an unheard of amount of money for anyone to pay for a single photograph.

The photograph was called The Manger, and the photographer was a woman named Gertrude Käsebier.

But before I tell you more about Gertrude Käsebier, let me first tell you a little bit about the type of photograph that sold for $100. It was a picture of a woman, but it wasn’t a standard portrait of a woman. You see, it was done in the Pictorialist style.

Now, Pictorialism was a movement that had started in Europe in the late 1800s. It was a response to the idea that a photographer was not a true artist.

I think people had argued ever since photography was first popularized in the 1840s whether or not a photographer was merely using a mechanical device to record the world around them, or whether they were really doing what an artist did.

People argued that a photographer, well, they were taking a picture of the scene in front of them, so it was necessarily realistic. The photographer had no say in what went into the photo, or at least that’s what people argued.

But an artist, on the other hand, well an artist first spent time thinking about what they were going to depict in their final artwork, visualizing it in their mind’s eye. Then, they picked up the paint brush and created the artwork to match what they saw in their mind’s eye.

For example, the argument was that if a photographer was taking a landscape scene and then saw fence posts standing in the way of the beautiful mountains beyond — well, people said that the photographer was stuck with taking the fence post and the mountain in the scene, where as the painter could decide whether or not to include the fence post when they made the final painting.

But of course photographers argued that they weren’t stuck with the fence posts either; they could manipulate things in the darkroom to make the final scene whatever they had envisioned in their mind’s eye. So photographers said that their process was very much like what people who were typically thought of as artist.

Pictorialist photographers went even a little farther to prove this. They would typically start with themes that might have been seen in paintings — maybe a theme from classical antiquity, or maybe from the Bible. They would then set up the scene that they were going to take, even using people dressed in costume if necessary, to create the basis for the photo that showed the scene that they saw in their minds.

And that was just the beginning of creating the final Pictorialist photo. Once the photo had been taken with the camera, the photographer with then go into the dark room with the image and make the final Pictorialist photo.

They would manipulate the image adding atmosphere — maybe soft focus effects; maybe using tricks to emphasize lights and darks and contours and shading — creating the final photograph that evoked a mood and stirred in the viewer the same kinds of reactions that the viewer might have to a painting.

The Manger by Käsebier is an outstanding example of this kind of Pictorialist photo. In the image we see a woman seated in what could be a barn and she’s cradling a bundle in her arms. She’s dressed in a gauzy white veil that flows over her shoulders. The whole scene is draped in soft focus haze. We can’t make out any of the woman’s features, but this is not a portrait of the woman who posed for the photo, but rather it’s meant to be a figure of a woman who evokes the idea of the Virgin Mary sitting in the manger, cradling the baby Jesus in her arms.

Gertrude Käsebier actually manipulated that final image quite a lot . The Library of Congress, in its archive, happens to have a version of the original photo that Käsebier took before she manipulated into the final The Manger artwork. In the original image you can actually see more details, like the facial features on the woman, the nails on the wall behind her, etc., things that are all in soft focus in the final image. What we have in The Manger is a work that is moody and atmospheric; we get a sense of peering into the manger looking at the Virgin Mary just after the birth of the baby Jesus.

Which is another thing — because we do have that understanding that this woman represents Mary, we look at the image, and we see a woman cradling a baby in her arms. But in fact there was no baby. Käsebier posed a woman with just a bundle of cloth in her arms.

And that’s kind of the point of Pictorialism: the photographer takes a photo of a real scene, but then manipulates it in the darkroom to create the final photographic artwork.

Gertrude Käsebier was a true master of this style. She had learned this technique in Germany in the 1890s around the same time that another American named Alfred Stieglitz had also learned about Pictorialism.

Stieglitz had brought that idea back to United States in the early 1890s and spent the next decade promoting this idea of artistic photography to American audiences.

When Stieglitz saw Käsebier’s work he was astounded. He touted her work, proclaiming her one of the best, if not the best photographer around in the late 1890s.

By 1902 Käsebier and Stieglitz had joined forces. Along with a photographer named Clarence White and several others they founded a new American Pictorialist group called the Photo Secession.

For the next ten years this Photo Secession movement leads the way for photography in the United States. Gertrude Käsebier becomes famous around the world for her beautiful Pictorialist artwork as well as her portrait and studio work.

But around 1912, Käsebier and White begin to have some disagreements with Stieglitz. Stieglitz has become interested in another style of photography, and his work starts to move off in a different direction.

Käsebier in particular has a huge falling out with Stieglitz. She, and then Clarence white, and then some others from the original group all quit the group

Käsebier and White eventually go on to found another Pictorialist group in 1917, but by that time Käsebier is 65, and she’s starting to wind down her career a bit. Although she’d only been a professional photographer for about twenty years at this point, as she hadn’t started her career until she was in her late forties.

Now remember that Käsebier 1899 was the most successful photographer in the United States.

It was her artistic work which sold for the watershed price of $100, a moment when American Pictorialism photography really came into its own and started to become accepted more widely.

So why, when you look in the history books, don’t you see more of a mention about Gertrude Käsebier?

Well, I think that can be traced to that falling out she had with Alfred Stieglitz. By the time the history books are being written about photography in America in the late 1930s and early 1940s, Gertrude Käsebier has died, and Clarence White has also died, and it’s Alfred Stieglitz who is writing the history. He had moved on from Pictorialism later in his career, and unfortunately I think that’s reflected in the history that Stieglitz writes, where Käsebier’s work is marginalized.

That’s really too bad.

Gertrude Käsebier … her work … her accomplishments … her contributions to the field of photography deserve more recognition.

I’ll be coming back to Käsebier in future episodes in the podcast. But for today I’ll just leave you with one idea: if you ever read a comment that women can’t be real artists or real photographers, tell them about the moment when artistic photography in the United States first got taken seriously … all thanks to the skill of a woman photographer named Gertrude Käsebier and her $100 photo.

Now on my website I’ll put links to the two versions of The Manger so you can compare for yourself sort of the before and after versions, to see what magic a pictorialist photographer did in the dark room to create the final pictorialist photo. Visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “P”, number “3”, photographers.net.

Or, drop me a line at podcast “at” p3photographers.net

That’s it for today. Thanks for stopping by! Until next time, I’m Lee and this is Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

3 thoughts on “02 The $100 Photo”

Comments are closed.