Notes

A big thank you to Sarah Weatherwax from The Library Company of Philadelphia for joining me again today to discuss a little more about Gertrude Saÿen’s life, particularly her husband, Edward M. Saÿen, Jr. and her son, Harrison Sayen, and the puzzling aspect of what Harrison did after his mother died.

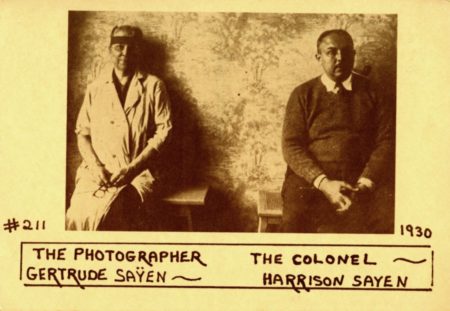

Speaking of Harrison Sayen, here’s a copy of that curious photo from the University of Pennsylvania Digital archives that Sarah and I mention in our conversation. The photo is from 1930 and shows Gertude Saÿen, “The Photographer” and Harrison Sayen (her son), “The Colonel”. Notice that their last names are spelled differently and there’s no indication that they are mother and son; the distance between them is interesting, as it seems from our vantage point to be representative of their seemingly distant relationship at the time of her death in 1941.

Sarah and I discuss that it’s also a bit odd that Gertrude Saÿen doesn’t show up in the Philadelphia directories as a photographer until the 1930s; instead, her husband Edward is the only Sayen listed as a photographer in the directories before his death in 1928

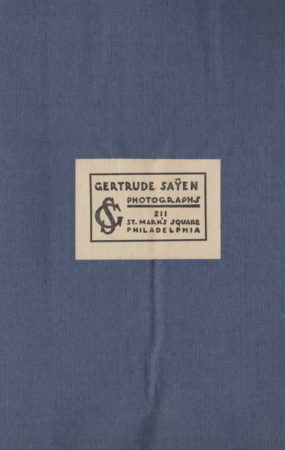

However, here’s a repeat of the 1920 photo book of Betty Ann Hunt that The Library Company in Philadelphia has in it’s collection; note that the signature on all the photos shown in the various books, as well as the imprint mark at the end, clearly indicate the work was by by Gertude Saÿen, not Edward.

1920 Betty Ann Hunt photo book (courtesy The Library Company of Philadelphia).

The Library Company of Philadelphia has also posted another photo of Betty Ann from that book on their website here.

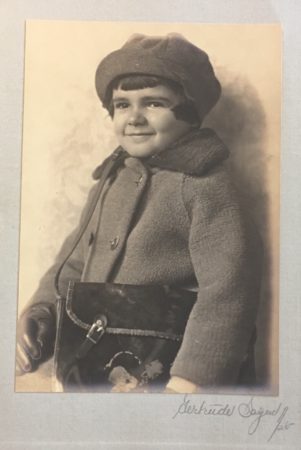

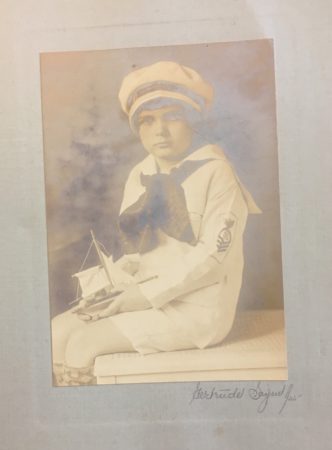

Here are photos from the 1925 Herbert Dwight Holcomb, Jr., the one my husband and I found on eBay last year. As I mention in this episode, it’s amazing how there are materials available on the Internet to trace this little boy’s life and tragic death. But in these photos, he’s remains a little boy with a toy or two, with the whole world in front of him:

Note that Gertrude Saÿen’s photographer mark/stamp on the last page of Herbert’s book is the same as the one found in Betty Ann’s book, even though the covers are different.

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- Ancestry.com (census records, city directories, and more; paid account required – Visit

- Family Search website has U.S. Federal Census and more; free account required – Visit

- Geneologybank.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- The Library Company of Philadelphia website – Visit

- Newspapers.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Newspaperarchives.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Peter Palmquist database at the Yale Beinecke Library – Visit

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.

Support for this project is provided by listeners like you. Visit my website at p3photographers “dot” net for ideas on how you, too, can become a supporter of the project.

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host, Lee McIntyre.

In today’s episode, it’s part 2 of my conversation with Sarah Weatherwax, curator of Prints and Photographs at The Library Company of Philadelphia, as we continue our discussion and try to unlock some of the puzzles around the story of the wonderful early 20th century photographer, Gertrude Saÿen of Philadelphia.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net.

That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers “dot” net.

*******

Today we’re going to tackle part two of Gertrude Sayen’s story. And I’m going to bring you part two of my conversation with Sarah Weatherwax, curator of Prints and Photographs at The Library Company of Philadelphia.

As I said, in part one, the library company wound up with thousands of Gertrude Sayen’s negatives and prints, as well as ledger books from her studio. But as I mentioned in a teaser for today’s episode, the reason The Library Company of Philadelphia wound up with that collection is not necessarily as straightforward as you might imagine.

First, I just want to recap part one: we met Gertrude Sayen and discovered that she’s responsible for some beautiful portraits (taken mainly of children) in her studio between 1913 and 1941 in Philadelphia. There are examples of some of her wonderful output, that are not just prints of the beautiful photographs, but also wonderful multi page, hand-bound photo books that include photographs of a single child shown in multiple poses and outfits and marked with the name and the date that the photos were taken.

Now as we pick up my conversation with Sarah today, Sarah and I are discussing Gertrude’s husband, Edward Sayen Jr, and what part he may have had in the photography studio.

…

Lee M

… now when they got married … certainly in the census is before 1920 … He is not a photographer, correct?

Sarah W

That is correct. H e is primarily only listed as a wholesale carpet dealer.

Lee M

And then suddenly, in 1920 [in the census], he’s listed as a photographer. And as we were talking, I have noticed that in the Philadelphia directory, at least in 1915, which is after Gertrude would have opened her studio, he is listed in the directories as a photographer, not Gertrude. And I just — I’m not sure what to make of that. So I need to make a little more investigation. I want to do the deep dive, as I said, into the directories to see if I can figure out when she starts being listed, if it’s before her husband dies. Her husband, then, is in the 1920 census [as a photographer] but by 1930, he’s actually passed away. I believe he dies in 1928

Sarah W

Yes, he dies in 1928.

Lee M

And he dies of a heart attack or something like that, I think, is it?

Sarah W

Yeah.

Lee M

So and that leaves just her and her son, Harrison; the only family member that surviving in her immediate family is her one son, Harrison. So I guess she is living with him or down the street from him in 1930? I’m trying to remember now, because, — or is he … he’s actually he’s not living with her …

Sarah W

Yes, in 1930 she’s listed in the census as living alone, as being a widow and as a. photographer.

Lee M

OK. okay.

Sarah W

He goes away … let’s see .. he was born in 1898.

Lee M

OK.

Sarah W

He does go away. I think she actually served in World War I. And he went to Williams College up in Massachusetts. And so by 1930, he’d be well into his 30s … he;d be 32, 33, three years old. NO, he was not living in Philadelphia with his mother.

Lee M

But then in 1940, though, — well, first, I guess why I thought they were living together in 1930. Because there’s a picture that’s identified as being from 1930 at the University of Pennsylvania. That is a picture of her sitting on a bench sort of in the same frame as Harrison, but they’re not really interacting with each other.

Unknown Speaker

Yeah, it’s such a bizarre photo.

Lee M

So I’m not sure what to make of that either

Sarah W

Yeah. Now that i’m looking at it in the 1940. Census, I see that you are correct. Harrison, her son, is listed as living with her in 1940.

Lee M

OK..

Sarah W

He’s 41 years old at that point. He never married. So he didn’t set up a separate household with his own family. So I don’t know if 1930 was just that he happened to not be there that particular year, or if there was a gap of time when he was living somewhere else. And by 1940, he had moved back home.

Lee M

Right.

Sarah W

It sounds like they had sort of a torturous relationship between the two of them. Sort of love-hate …

Lee M

So let’s talk a little bit about that. Because that sort of factors into what happens right after she dies im 1941.

Sarah W

My understanding is that there was definitely some problems between the two of them. When she died in 1941. She actually was settled … she was 67 .. And her son was in his early 40s. And he was living apparently in Virginia. And he was unwilling, even though he had apparently no interest in returning to the family home, Philadelphia —

Lee M

Right.

Sarah W

He did not want to sell the house. So he instructed his attorneys to simply close the door. And he hired somebody in the neighborhood to kind of look out for the house to probably shovel the snow off the sidewalk to make it not look abandoned,

Lee M

Okay

Sarah W

…o n the off chance that she would want to come back to it at some point. He lived until 1977. And never came back to the house.

Lee M

He was still the owner, right?

Sarah W

Yeah, yeah.

Lee M

And somebody offered to buy in a couple a couple of times, I think. But he would never return their letters or something. Right?

Sarah W

Right. options to get rid of it if he wanted to, but for whatever reason – a sentimental attachment to it, or some kind of attachment to it. And he died 35-36 years after his mother, and he had never been back.

Lee M

Wow. So I mean, it’s just so incredible, he would have this house for so long. And, well, his mother had died at home, right, so I guess you could argue that there was a painful memory there, but to spend all that money on the upkeep and never actually set foot in it again. But then after he dies,

Sarah W

my understanding is that after he died, he didn’t have any direct heirs, because but he didn’t marry and have children, but whoever inherited the house ‚which is probably some extended family member — they decide they wanted to sell the house, I believe that they went in and took things that they thought were valuable to sell that belonged to them, and then just decided to sell the house and the remaining contents. And someone purchased the home, moved in — or was about to move in — and realized that a lot had been left behind. And realized, you know, the contents of Gertrude’s studio there. And so then at that point, the new home owners contacted a woman in the neighborhood of Getrude’s home, who was sort of seen as the unofficial neighborhood historian, to ask if she would be interested in taking all the photographs and the negatives and the records. They realized that there was some value, maybe not a monetary value, but stremendous historical value in them. And this woman in the neighborhood was like, Well, yes, of course, this is important material there. So she’s the one that sort of took the material on and it was from her that The Library Company acquired the, material in the late 1980s. But she tells the story of going into the home for the first time with the new owners a nd realizing that, you know, it was like a time capsule from 1941 when Gertrude died … that there was, you know, a teapot still sitting on the table. The calendar was still turned to February 1941, which is a month that she died. There was a pile of newspapers from 1941. It was just sort of a really weird feeling to be in a place where almost the last person who had been in the home was the photographer.

Lee M

Right. And that’s just incredible. And then it’s incredible that — whoever the family was, who went in and took stuff out — at least they didn’t throw anything away. So for studio materials, it’s amazing that they just left it all there. And then the new owner, you know, thought, again, not to throw it away, thank goodness, and thought that somebody somewhere might find some value in it. But that’s just incredible that her son just had it sit there and apparently never even went in and cleaned up. You know, the teapot, etc. Wow. It’s just it’s sort of mind boggling.

Lee M

As far as we know, her son was never a photographer, although I think there wasn’t mentioned that he was on the board of some sort of stereoscopic organization or something like that. Did you run across anything that indicated that he had anything to do with photography?

Sarah W

I should say no. And that’s interesting. I didn’t know that reference.

Lee M

Okay. I’ll send you that clip. I don’t remember exactly. But it was

Sarah W

Yeah, I think if he had a career, it was in the military, which doesn’t preclude that he was interested in photography.

Lee M

True.

Sarah W

I think he was an officer in the military

Lee M

OK. Oh – he was the president of the Winnick Stereoscopic Processes of New York from 1930 to 1940, according to his obituary. So, it’s not clear – so maybe that’s what he was doing in the 30s? He was off somewhere. Maybe he was doing something with photography.

Sarah W

Possibly, yes.

Lee M

So because .. I mean .. her — Gertrude’s, brother in law was an inventor and an artist. H. Lyman Saÿen, Edward’s younger brother, he was an artist and inventor of some sort of X-ray process. And he was a judge of a photography exhibition in Philadelphia. And another member of the panel was actually Alfred Stieglitz [a famous American photographer]. So …

Sarah W

Oh wow, you have really interesting stuff; I want that for my researh files!

Lee M

Right, I’ll send you everything I’ve got! But see, you’ve got all of her studio stuff, though! You’ve got all those letters and those ledger books, which is very exciting for me that stuff like this exists. I mean, usually you don’t find this stuff has been preserved, you typically find that some family member or distant relative, thinks, “eh -, we’ll just throw it all out.”

Sarah W

Yeah, true.

Sarah W

But the might be [H. Lyman Saÿens] where Gertrude learns photography.

Sarah W

I mean, it does seem like … I feel like some of the society columns that I mentioned where it said, you know,”Miss So and so” went with “Miss So and so” and “Mister So and so” … I felt like I saw different members of the same family before she was married to Edward, that they were sort of roaming around together. So that might be a connection to her future brother in law,

Lee M

I wonder now.

Lee M

Right. And then, I believe, that brother in law, hemoves to Paris, with his wife. And then they come back at the start of the war, World War I, and then he dies in 1918. But I don’t think he dies as a soldier. I pretty sure he dies at home. But he’s fairly young in 1918. So, but I haven’t really investigated him either. So another area for investigation, because he didn’t do photography, but he’s on this panel to judge photography. So maybe he did do some photography, but it’s not in any of his official bios, which talks about him as being a painter.

Sarah W

You would think that they would get judges that had some — I mean, even if they weren’t photographers themselves — that had some some photography background.

Lee M

Right. Right.

Sarah W

Some reason to think they were worthy of judging others.

Lee M

That’s right. That’s right. And I mean, certainly, I mean, I don’t know if it’s true then … But well, no, I mean, I think, Rene Magritte did photography to take pictures of stuff that he would eventually be interested in painting pictures of; not to paint and replicate photo, but to sort of, you know, take ideas from the world to remind themselves of something. So I know, other photographers did that. I mean, other painters did that, too. And actually, my aunt is a painter. And she taught me how to do photography when I was a kid. But not that she did photography for her art, but she did photography, again, to sort of as references and things like that.

Sarah W

That totally makes sense. And also, I’m just wondering, 1918 I think that’s right about when the influenza epidemic was.

Lee M

True. That’s true. So he could have died from that.

Lee M

Yeah, if he died young and wasn’t in the war, he sadly could have been a victim of the flu. Absolutely. Absolutely. So yeah, I’ll have to see if I can find his obituary, to see if it says more about that, I think what I, what I’ve seen is unfortunately, based on Wikipedia for him, and then I think one other reference about that thing in the judging the photo contest. So lots of curious things.

Lee M

But, you know, again, just trying to understand, Gertrude seemed like she was a very successful photographer, running the studio, seemingly on her own, except for this anomaly that her husband is the one listed as a photographer in 1920, in the census. And so I guess this idea that women couldn’t sort of be named on the studio… but I certainly have run across a lot of women who are named on the studio, even in Philadelphia in 1915. So I’m not quite sure what to make of her name not being listed there in the directory.

Sarah W

I wonder if at all, I mean, was it a business directory? Or was it a residential directory, do you remember?

Lee M

This is a sort of the combination. In modern terms, it would have been white pages and yellow pages. OK, perhaps not “modern”. But, you know, when I was growing up, there was the white pages and the yellow pages. And so in the white pages residence section, Edward Saÿen, Jr. is listed as a photographer. And unlike some small town directories, there isn’t a parentheses to say the wife’s name. And Gertrude isn’t listed separately. And then in the Photographers’ list, I forget how many there are, there are a ton of photographers, maybe 80 photographers in that directory in 1915, in Philadelphia, but there are women listed there, and maybe 10 of them are women. And they’re listed with their names. But then Edward Saÿen, Jr. is listed as a photographer in this what I call the Photographers’ list in the business directory.

Sarah W

And I was just wondering, because probably not a lot of people were doing anything, at least by 1915, were doing photography in their homes. So I’m wondering — maybe I just don’t want to admit that Edward could be the photographer behind this. But I’m assuming it may be because, you know, he was a household head, right. So in the directories, I’m not sure at what point they would list people who weren’t the household head. So I’m not sure.

Lee M

Oh I see. I see what you mean.

Sarah W

Certainly other people living in the household would not be listed. Yeah, that’s that’s one of the drawbacks of using the directory, around [the diretory] not picking up everybody. I’m wondering if that might explain the sort of the residential part. You know, he’s listed, I would say, because he was the household head for that household, and in that hjousehold was a photography studio, you know, if someone wasn’t being very careful, or just, you know, that was an insignificant difference to them that it wasn’t actually Edward doing it. It was his wife.

Lee M

Right. Right. That’s true. So maybe,

Sarah W

So that might explain the sort of shorthand formula on that census taker’s part (i.e.) that’s what you do. And then you go to the next hous. That’s right. But that doesn’t explain in the business section why he would have had his name there.

Lee M

Right. I mean, it could be I suppose that if she had the studio in the home, they didn’t want to make it look like it was she was there on her own or something. I don’t know. I mean, I could make up lots of stories … I’d have to go back because in that same …. so I’m just looking …. there are 10 women in the Photographers’ list in 1915 that are listed in that “yellow pages” kind of section. But I’d have to go back and see how they’re listed in the residence section. But then they are listed in the Photographers’ list. And at least a couple of them, I have a note on this list of these photographers that at least two of them are married. But it’s their name that’s in the Photographers’ list … I take it back, the two that are married are actually married to photographers. So it was really striking actually to sort of look at this list, and realize that Gertrude is not there. Even though she did start — I mean, there was an article in the newspaper that said she started her career in 1913. And your ledger started in 1913. So that sort of matches that. But certainly no indication in anything that he was doing any kind of photography and, you know, the her mark that on these photos that we have the examples of the prints of it’s her who has signed them and her who has put it on her stamp on it.

Sarah W

Yes, very clearly. Yep. And all the envelopes that people were returning, you know, there proved right very clearly that it was Gertrude Saÿen.

Lee M

Right.

Sarah W

It doesn’t say the “Saÿen Studio”, it says Gertrude Saÿen.

Lee M

Yeah. So I don’t know. It’s, it’s a puzzle. So there’s still be more to uncover thing at some point. And one of the things that I want to do is go more carefully through the Philadelphia directories. During the years that she would have been active to see what happens to the name of the studio, particularly after 1928 when Edward dies, so it’s definitely can’t be his name in the list anymore.

Lee M

Any final thoughts about her life career?

Sarah W

I have to say from from talking to you, it makes me realize that there’s so much more work that we could be doing with the collection and learning more about her. You’ve told me things I did not know. And I hope I told you things that you didn’t know. And it was just one of these cases of there’s so many interesting women photographers, historical women photographers that we don’t know a lot about. And once you just start to do a little bit of digging, great stories emerge. And then we talk to other people, they have little bits and pieces of the story and it sort of a building blocks into something that is just fascinating.

Lee M

I completely agree. I mean, I think one of the archivists here at the University of Washington, Nicolette Bromberg, commented once that she finds as she starts to uncover these stories, she feels like she’s saving lives, because she’s resurrecting these stories of these women who have been overlooked and forgotten. And yet, you learn that they were just fascinating in terms of the work they did, that kinds of photographs they took, and even just the kind of lives they lead. So Well, as you know, it’s my passion to do this, which is why I’m doing this podcast.

Sarah W

Really happy that I could be part of it, because it’s a real interest of mine as well. So it’s great to know that you’re out here doing that kind of stuff.

Lee M

That’s right. Well, it’s always exciting for me to connect with somebody like yourself that has the same kind of interest and passion. It’s really been a great pleasure. I really appreciate your taking the time.

Sarah W

Thank you for asking me.

*******

[July 1, 2019: The rest of the transcript is coming soon!]

******

That’s it for today. Thanks as always for stopping by!

Until next time, I’m Lee and this is Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.

1 thought on “43 – Meet Gertrude Sayen – Part 2”

Comments are closed.