Notes

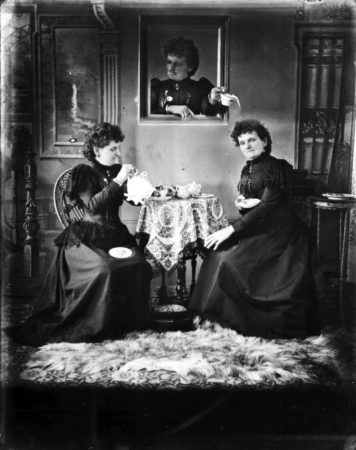

It isn’t your standard “selfie” – all 3 figures in this trick photo are the photographer herself, Hannah Maynard:

This is just one example of Hannah Maynard’s marvelous photography. I’ve included a link in the links section below to more of her photos that are available online at the Royal BC Museum Archives; I’ve also added some to the board for this episode on Pinterest.

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- Digitized copies of Hannah Maynard’s photos in the online Royal BC Archives – View

- The Magic Box: The Eccentric Genius of Hannah Maynard by Claire Weissman — Buy

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host, Lee McIntyre.

In today’s episode I’m gonna take you to the slightly surreal world of 19th century photographer Hannah Maynard.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers.net.

Today I want to introduce you to the 19th century photographer Hannah Maynard.

Hannah Maynard was born in England, but she moved to eastern Canada in the 1850s when her husband decided to move the family there so he could open up a shoe business in eastern Canada.

He later got gold fever and left Hannah Maynard and the kids in eastern Canada while he went west to see what fortunes he could find.

While she was alone with the children, she took herself off to a photography studio and asked the photographer to teach her how to be a studio photographer.

So by the time her husband came back and announced that the family would be moving to Victoria in British Columbia, well, Hannah Maynard had made up her mind to become a photographer.

In 1862 she opened up a studio in Victoria, British Columbia, that she ran for the next fifty years.

She was very successful doing both landscape photography, as well as a lot of studio photography. Her specialty in the beginning was really taking images of children, and she photographed children in that town, as I said, for fifty years.

Even though she was doing studio photos which were of a particular type, she was experimenting in ways that other photographers didn’t do, incorporating mirrors into her photos early on, taking reflections of the people, but also using mirrors to represent water, posing the children as though they were at the edge of a pond in the middle of a forest, using backdrops to illustrate the forest and the mirrors to illustrate the water.

She used a variety of equipment and techniques over the years. In the 1880s she used a style called Gem photography, which was a very particular small-scale photo that allowed you to put it easily into a piece of a jewelry, like a locket or something like that.

Not only did she market these kinds of images for jewelry, she also use them for yearly advertising for her business throughout the 1880s, creating something she called the “Gems of British Columbia.”

These were collages, or really creative montages, of all of the images, all the faces of the children that she taken photos of during the previous year.

But she always arrange them in some sort of scene or a depiction of an object.

For example, for her “Gem of British Columbia” in 1887, Hannah Maynard arranged all of the children’s faces to form the shape of Queen Victoria’s crown, in honor of the Queen’s golden jubilee that year.

She also has images where there’s a fountain and the children’s faces are flowing out of the water of the fountain.

She incorporates the idea of the mirrored images, creating reflections of the children seated by the water.

This is all done in the darkroom, painstakingly constructing these montages year after year, and incorporating the previous year’s montage, so at the end of ten years her final montage — her final “Gem of British Columbia” — contains 22,000 images of children.

Now in the 1890s she started to experiment more with multiple exposures, some of which are slightly surreal.

I think my favorite photo is really one that I called “The Mad Tea Party.”

Now when you look at it at a quick glance, it looks like it is a depiction of three women having a tea party in a 19th century Victorian parlor.

There’s a woman on the left-hand side pouring the tea; there’s a woman on the right-hand side holding a teacup; and there’s a woman in the middle of the table …

But then we realize, well, wait. That woman in the middle, she’s not actually at the table, she’s in a photo that’s framed above the table that’s hanging on the wall.

But she’s not just in the frame, she’s actually leaning out of the frame. She’s got a teacup in her hand, and she is dumping the contents of her teacup on the woman who is seated at the right-hand side of the table.

That’s all surreal enough, but then you realize that all three of the women are Hannah Maynard herself. She has taken three images of herself and incorporated them seamlessly into this image that seems to show three women at the same table.

It’s really amazing. I mean, you can do multiple exposures today on the computer in the “digital darkroom”, but it’s hard to actually manipulate them so that they’re seamlessly integrated. The lighting has to be just right, or you have to manipulate them just so. On a computer that’s hard to do, and so I really tip my hat to Hannah Maynard for doing this so well in the darkroom in the 1890s.

Now in 1897 Hannah Maynard seems to have given up her experimentation in her darkroom for these multiple image experiments.

But that was the year that she actually went to work for the Victoria police department.

She started taking all of their mugshots.

They would send the all the criminals under arrest, they’d bring them down to her studio, and she would be responsible for taking pictures of them.

They requested both a full face and a profile shot..

After awhile she actually starts experimenting and she winds up using a very specially constructed mirror hung. It appears in the pictures over the left shoulder of the person who was accused of the crime. The resulting photo is just one photo, but it shows both the full face view as well as the profile view that you can see in the mirror.

Working in this way meant that Hannah Maynard could take just one picture instead of two, which saved on time and materials, but still delivered what her client wanted, which was the profile and the full frontal view.

I mean, that’s genius, right? She’s now getting paid and applying another aspect of her creativity while getting paid.

Now I had seen Hannah Maynard mentioned in passing in a couple of general books on women photographers.

But I had never seen anything about the full range of her complete fifty year career until I ran across a book called The Magic Box: the Eccentric Genius of Hannah Maynard, written by a woman named Claire Weissman Wilkes.

I based this podcast on material from that book, as well as material found on the Royal British Museum Archive website. The Royal British Museum is in Victoria, BC, and it houses an extensive collection of Hannah Maynard’s photos, glass plate negatives, and some written material as well.

I’ll put links to information about both the book and the archive on my website.

I really recommend if you have a chance to check out both the book and the website, so you can get a much broader sense of just how innovative Hannah Maynard’s photography really was.

And it was in all aspects.

I mean, she was a studio photographer, so there are the studio portraits, which are very clever, sometimes involving those props like the “pond” which was really a mirror.

And sometimes she’s just got some clever printing and matting, particularly with some full figure fashion statements.

Of course, there are all her “Gems of British Columbia,” which show off not only her skills as a photographer and portrait artist of children, but also her real savvy as a businesswoman doing marketing for her business.

There are multiple examples of the police department mugshots that I mentioned, as well as numerous other photos that are slightly surreal involving her relatives and her dead relatives. You’ll have to check out the website to see what I mean.

And keep in mind that she opened her studio in 1862.

Just think of all the changes in technology that she saw over her fifty year career, all of which she would have had to not only learn but master in order to become as accomplished as she clearly was, from the photos that survive.

Hannah Maynard was truly a remarkable woman, as well as being a remarkably talented artisan photographer.

For more information about any of the early women photographers profiled on the podcast, visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers.net.

Or, drop me a line at podcast “at” p3photographers.net

That’s it for today. Thanks for stopping by! Until next time, I’m Lee, and this is Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

1 thought on “04 Slightly Surreal World of Hannah Maynard”

Comments are closed.