Notes

An early pictorialist-style portrait by Margaret DeM. Brown of “MCB”, exhibited in 1917. My guess is that “MCB” — the young model in the photo — was Margaret’s younger sister, Mary C. Brown.

One of Margaret’s early newspaper ads for her new studio in Poughkeepsie (from the Vassar Miscellany Newspaper):

Here’s the photo of FDR that I saw at the Library of Congress started me off on my search to discover just who “Margaret DeM. Brown” might be:

For more photos and other related material, check out the board I’ve created for this episode on Pinterest.

CORRECTION: A descendent of one of Margaret DeMotte Brown’s relatives, C.M., has kindly pointed out that in my telling of the story of Margaret and the money she inherited, I mistakenly put her aunt in the wrong family. C.M. writes, “Hiram Price Dillon’s wife Susan as a sister of Margaret’s mother Ellen (Nellie). However, there was not a daughter Susan in William Holman DeMotte’s family. The Aunt Susan, was Susan Finley Brown, wife of Hiram Price Dillon. She was Margaret’s father, William Finley Brown’s, sister, not her mother’s sister..” My apologies for the error – I was not reading my research notes carefully enough, apparently, when I recorded this episode. Thanks, C.M. for catching that – much appreciated! 🙂

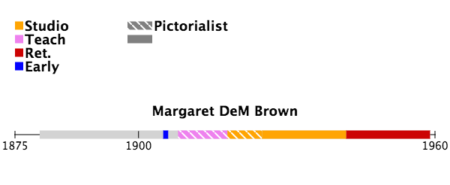

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- Essay on the Dutch Houses, including some of Margaret De M. Brown’s photos – Read

- Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley Before 1776, Helen Wilkinson Reynolds (Author), Margaret De M. Brown (Photographer), Franklin D. Roosevelt (Introduction) — Buy

- Prerevolutionary Dutch Houses and Families in Northern New Jersey and Southern New York, Rosalie F. Bailey (Author), [photos by Margaret De M. Brown] — Buy

- Dutchess county doorways, and other examples of period-work in wood, 1730-1830, Helen Wilkinson Reynolds (Author), [photos by Margaret De M. Brown] — Buy

- Helga and the White Peacock: A Play in Three Acts for Young People, by Cornelia, Illustrated by Margaret De M. Brown Meigs (Author) — Buy

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host, Lee McIntyre.

In today’s episode we’re on the trail of the photographer Margaret DeMotte Brown.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers.net.

In today’s episode I want to introduce you to a woman named Margaret DeMotte Brown.

Now, who was Margaret DeMotte Brown?

Well, I’ve ran across her by accident. In the Library of Congress there’s a photo by Margaret DeMotte Brown that shows a rather youngest Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Well, he seems younger and more relaxed than he seems in any of the photos after he becomes president of the United States. And, indeed, this is a photo of taken before he becomes president: the date on it is 1931.

In the photo we him sitting in a wicker chair. He’s holding a bunch of papers in his hand and in his lap.

He’s looking up and over to his right, looking at someone off camera. He seems very relaxed very happy.

The only notation on this photo was that it was done by a woman named Margaret, middle-name DeM. Brown— the middle name is spelled capital “D” lowercase “e” uppercase “M.” and asking turns out to be an abbreviation for her full middle name, DeMotte. I’ll try to refer to her as Margaret DeMotte Brown or just Margaret Brown. If I do call her Margaret Brown, I don’t want her to be confused with the woman who survived the sinking of the Titanic; her name was also Margaret Brown, but that’s not this Margaret Brown.

This Margaret Brown is a woman who was born on March 1, 1880 in the town of Jacksonville, Illinois. Her parents were William F. Brown and Helen “Nellie” Demotte.

Nellie’s father, William DeMotte, was a quite prominent educator. He founded the Illinois Women’s College, the Illinois School for the Deaf, both in Jacksonville, Illinois, as well as other schools for the deaf around the Midwest. He either was responsible for founding them or running then.

He was a great believer in education for women, and he insisted that his daughters all get an education. In fact, Margaret’s mother, Nellie, graduated from the Illinois Women’s College.

He would’ve been a fascinating man to get to know in his own right. He had so many different experiences with education and systems that he invented.

But then he also had an interesting back story episode during the Civil War.

In 1865 he was actually posted in Washington DC. In April that year he decided to buy tickets so that he and some of his men could go to Ford’s Theater when Lincoln was going to come to a performance. He bought tickets for the box across from the presidential box, hoping to catch a glimpse of Abraham Lincoln. Unfortunately, Lincoln was seated so far back in the presidential box that they never actually got sight of Lincoln — until after a shot rang out. Because yes, this was the day that Lincoln was assassinated. William DeMotte was actually a witness to that assassination. So that must have made for some interesting conversations around the dinner table when he would talk about his experiences during the war.

But that really has nothing to do with Margaret and her photography, so let me get back to Margaret and her family.

Now Margaret grew up in Jacksonville. She was the eldest of several children.

In 1896 her mother takes her to Topeka, Kansas to visit her aunt and uncle and her cousins there.

[Corrected text] Margaret’s father was William F. Brown, and his sister was a woman named Susan Dillon. Susan Brown had married a man named H. P. Dillon. Aunt Susan and her Uncle H. P. hosted Margaret and her mother all that summer of 1896, when Margaret was sixteen years old. That was a summer that there were a lot of social parties and things, because H. P. Dillon was quite prominent in society, so his family was quite well-to-do, and his children were getting the full society treatment. Eventually his daughters come out for the season and marry quite well.

Now Jack, who is H.P. Dillon’s son, Margaret’s cousin, spends the summer of 1896 squiring Margaret to all these parties all over town. All kinds of social notices indicate that probably Nellie and her sister Susan are plotting to get Margaret a good marriage.

Unfortunately, Margaret’s father’s health starts to fail shortly thereafter, and by the late 1890s William F. Brown has moved his family to Citronelle, Alabama.

In 1900 we see that William F. Brown and Nellie Brown are living in Citronelle, Alabama, with their daughter Margaret, who is 20, their daughter Frances, who is 12, and their daughter Mary, who is 5.

William Brown’s health was bad, and Citronelle turns out to be a town that people might have gone to for their health. There were resorts there. There are advertisements in the paper promoting that is a health benefit to go Citronelle, Alabama. William Brown does recover his health to the extent that he does live for another twenty years.

Margaret in 1900 in the census doesn’t list any kind of profession.

But in 1905 we start to see her advertising photos for sale in various little photo journals that are circulating among people who are professional photographers and photography hobbyists. In 1905, Miss DeMotte Brown is advertising photos of the south — typical scenes of the south — black and white prints available for sale.

So she’s clearly started doing photography sometime while she’s in Citronelle.

When we get to the 1910 census, though, we see that she’s actually move back to Jacksonville, Illinois. Now her grandfather had been instrumental in the Illinois School for the Deaf in Jacksonville, and I don’t know for sure if he was still there, or if he was off running another school for the deaf at that point. But Margaret, between 1905 and 1910, has actually taken up a job at the [Illinois] School for the Deaf teaching photography .

So the 1910 census is kind of interesting because it lists her as being in Jacksonville and living as a lodger in a boarding house, teaching photography at the school for the deaf.

Another person living in the same boarding house is her younger sister Mary. Now Mary is only 15, but she’s now not living with her parents in Citronelle, but she’s moved back to Jacksonville to live with her sister Margaret.

Back in Citronelle, though, the other sister Frances actually is now 20 and she’s listing herself as a photographer as well. I haven’t been able to track down if Frances Brown actually practiced as a professional photographer or just did it as a hobby. She actually gets married shortly after and she starts building a very large family — I think she ultimately she has 8 children. So, she does not have a lot of time early on to continue doing photography, I wouldn’t think.

But back in Jacksonville, Margaret is teaching photography at the [Illinois] School for the Deaf.

Now in addition to teaching photography, she’s also become interested in an artistic style of photography called Pictorialism. By 1915 she’s started to regularly exhibit pictorialist works in exhibitions throughout the United States.

This interest in Pictorialism has actually prompted her in the summer of 1916 to go to New York to study there, and there’s an interesting notice in the Jacksonville Daily Journal newspaper in September of 1916 which – let me just read it to you. It says,

“… having secured a year’s leave of absence as a member of the faculty of the Illinois School for the Deaf, Miss Margaret DeMotte Brown will spend the time in art work in New York City. During the summer, Miss Brown studied in the east with a well-known illustrator and portrait artist, and she is to have a place in his studio during her absence from Jacksonville.”

OK, so Margaret is going to New York, and what she’s done is sign up to study in the studio with a man named Clarence White.

Now Clarence White was one of the preeminent pictorialists in 1916. In the early 1900s Clarence White, along with several other photographers including Alfred Stieglitz and a woman named Gertrude Käsebier, had actually established the very first American pictorialist group, the Photo Secessionists.

By the 1910s Clarence White and Getrude Käsebier have had a big falling out with Alfred Stieglitz, and the Photo Secessionist group has pretty much broken up.

Clarence White is still a big proponent of Pictorialism, as is Gertrude Käsebier, although her career is starting to wind down as she starts to wrap up her studio work.

But in 1917 Clarence White and Gertrude Käsebier start the Pictorial Photographers of America group, the successor to the Photo Secessionist group. [The PPA] is the preeminent pictorialist group in the United States in 1917, and Clarence White is president. Gertrude Käsebier is the honorary vice president, and Margaret DeMotte Brown is the corresponding secretary of the group.

So even though Margaret DeMotte Brown has been in Jacksonville for most of her photography career up to this point, she’s been very active with the pictorialist group to the extent where she is actually now part of the main pictorialist group in the United States. I mean, she is in with the movers and shakers of Pictorialism at this point.

She’s exhibiting with them, so in 1917 there’s a big pictorialist exhibition called the Pittsburgh salon, and Margaret DeMotte Brown actually exhibits a picture called “Portrait MCB”

It’s a beautiful picture of what looks like a young dancer. The description in the catalog says that it shows a woman in a white dress, standing before a dark curtain, effectively throwing into relief the delicate tones of the dress.

Now the idea of the pictorialists was such that a portrait didn’t necessarily have to be an identifiable portrait of a person, but more of an idea, an atmosphere. It had great tonal qualities, it had great lights and darks and shading, things that made it evocative of a painting more than a pure black and white photo. That was the intent of the Pictorialism movement.

Now I do talk a little bit more about the Pictorialism movement and Gertrude Käsebier in another podcast episode called Gertrude Käsebier and the $100 photo, so I’m not going to talk a lot about the specifics of Pictorialism here.

But suffice to say that Margaret DeMotte Brown’s pictorialist work was so exceptional that she is now at the upper echelons of the Pictorialism movement in United States.

At this point — in 1917 — Margaret DeMotte Brown is now 37 years old.

Now she’s been a teacher, and she’s doing this artistic work on the side. She’s not making a living from the artistic work, and she’s not running her own studio.

But in June of 1917 there’s a little ad in the Poughkeepsie, New York newspaper that Margaret DeMotte Brown is planning to open a studio in Poughkeepsie in the fall of 1917.

I have to wonder how much influence Gertrude Käsebier had trying to get Margaret DeMotte Brown to see that she wasn’t too old to reinvent herself.

Because you see Gertrude Käsebier had actually reinvented herself at the age of 37. When she was 37 years old, she was a married mother of three. But one day she announced to her husband, look, I really want to do art and photography, so I’m going to go off to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, and I’m going to study art.

This is unusual for a woman of that day and age to just decide to leave her husband and children home while she went off to study art. But that’s what Gertrude Käsebier did, and it wasn’t long thereafter that she opened up her studio, turning herself into one of the preeminent photographers of the early 1900s.

So I just picture in my mind Gertrude Käsebier sitting down with Margaret DeMotte Brown, saying, look, you’re not too old, I did when I was 37, you can do this! Take the plunge — open your studio.

However, in the fall of 1917, back in Jacksonville, there’s a notice in the paper that Margaret DeMotte Brown has resumed her duties at the [Illinois] School for the Deaf.

So instead of opening a studio in Poughkeepsie, New York that fall, she actually has just gone back to Jacksonville and resumed her teaching duties.

Who knows — maybe she was worried that she wasn’t going to make it and thought it was gonna be safer to go back to teaching.

Maybe she was worried about how much money was going to cost to open her studio and decided to go back to work a little while longer to get a little bit more money.

Or maybe there there’s some other reason that prevented her from opening a studio in the fall of 1917.

Now, if I was writing a novel about Margaret DeMotte Brown, and I put in this next incident that happens, well, people wouldn’t believe it. They would say come on, that’s so ridiculous!

Because it turns out that what happens in September of 1918 is that Margaret has the proverbial rich uncle who dies and suddenly leaves her an inheritance.

Remember Uncle H. P. and Aunt Susan from Topeka back from that 1896 social season that Margaret did with her mother? Well, H.P. Dylan unfortunately dies, and he dies leaving an estate worth a million dollars.

Now, most of that money goes to his wife Susan and his own children.

But he actually leaves a legacy to Margaret DeMotte Brown; he leaves her $1000, which in 1918 had the buying power of $17,000 today.

So she suddenly has enough money, that if she wants to go off and start that studio in Poughkeepsie, she now has the means to do it!

I mean, I don’t think I’ve ever run into anyone who’s actually gotten a rich uncle to suddenly up and die and leave them a bunch of money. That only happens in the books — unless you’re Margaret DeMotte Brown. And it happened to her in real life.

So in November of nineteen eighteen there’s an ad in the Vassar Miscellany News in Poughkeepsie, New York. The ad is slightly big and it reads,

“Margaret DeM Brown, Photographer. ”

She’s opened a studio now Raymond Avenue

The ad goes on to read,

“Miss Brown, a photographer whose work has been exhibited in New York in various museums throughout the country, has opened a studio here. Miss Brown approaches her work sympathetically, her main object being to make character portraits of her sitters, in their homes or at her studio.”

And that description of making character portraits at their homes or at her studio is exactly the kind of work Gertrude Käsebier did, particularly when she was starting out in the late 1890s. So again, I’ve got to wonder how much influence and how much inspiration Margaret DeMotte Brown had from Gertrude Käsebier for the kind of career she was carving for herself in Poughkeepsie.

So starting in November of 1918 Margaret Brown has a studio in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Her letterhead advertises different kinds of photography beyond just those portraits. She advertises taking garden pictures; taking interiors; taking illustrations; providing things from books for newspapers; all kinds of photography.

She has a close connection to events at Vassar, although she doesn’t work for Vassar College proper, but her studio is right on the edge of campus and she takes ads in that Vassar Miscellany newspaper in order to advertise her studio to give herself a wide range of work.

She also puts on special exhibitions of her artistic work, particularly in the 1920s when she is still doing more of the Pictorialism. In the 1930s she actually starts to organize exhibitions back in Jacksonville to celebrate her work and her development as a photographer.

She’s taking photos of all kinds of activities at Vassar. She’s taking yearbook photos. She’s also taking pictures for the Botany department — she has a whole study of ferns that she did at the request of the Botany department. All kinds of different things, including those very pictorialist-style portraits.

Now there is one version of one of these artistic portraits porches that survives, that is of a Mrs Reynolds, who is the mother of a woman named Helen Wilkinson Reynolds.

Helen Wilkinson Reynolds is a really important person in Margaret’s life when she’s in Poughkeepsie.

They were clearly friends as well as colleagues on several projects, and at one point Margaret and her mother, Nellie, live next door in apartment right next door in the same building to Helen Wilkinson Reynolds and her mother.

At one point Margaret take some beautiful outdoor portraits of Helen Wilkinson Reynolds’ mother, and provides not only a gorgeous triptych of this mother in the garden, seen in a really pictorialst soft focus atmospheric style.

But she also provide some black and white prints from that same photo shoot, which allows us to see the artistry that Margaret DeMotte Brown applied to her pictorialist photography, because a pictorialist photo would start with a black and white photo, but then in the darkroom add effects, create contrasts and emphasize shading to make it into this soft focus, atmospheric, final artistic portrait.

That’s what we see in this triptych of the pictorialist style portrait of Helen Wilkinson Reynolds’ mother.

Margaret actually collaborated with Helen Reynolds on a number of different projects.

One of the first things they did together was a book called Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley before 1776.

It’s a study of these Dutch stone houses that are a predominant style of architecture in that part of New York.

Helen Wilkinson Reynolds wrote the text for that book and Margaret DeMotte Brown took all the pictures.

Now they were working together – it was sponsored by the historical societies in the area, and they worked very closely with an historian who was also providing a lot of the funding.

That historian was the historian of Hyde Park, a man named Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

So before he was governor, before he was president he was the official historian of Hyde Park in very active with the historical societies in that area.

There are some surviving letters between FDR and Margaret DeMotte Brown about this project for this book, discussing not only how much payment she was going to get, and how it’s going to be paid, and the progress reports on the work itself, and where the pictures have been taken, all kinds of project related information in these letters.

There’s also a little bit of personal stuff as well.

In one of the letters FDR says to Margaret, oh, by the way, Mother would like you to come over to take pictures of our garden over the weekend, if we can arrange a time, so let me know.

You get a sense in terms of Margaret DeMotte Brown’s life in Poughkeepsie, and how she’s intertwined with a lot of different people and a lot of different areas, not just at the college but also at the Historical Society. Not just her friend Helen, but also people like Franklin Delano Roosevelt who, of course, goes on to become president of the United States.

She goes on to do more Historical Society books.

She does another book with Helen.

She does another book on the Dutch houses that covers a broader geographical area.

She also does a book of photos from Vassar College experimental theater production. The book is called “Helga and the White Peacock”. The play is actually being performed by the Vassar College experimental theater group, and the pictures of that Vassar College production are actually in the book.

Throughout the 1930s Margaret continues to have an active, thriving, successful studio. Again, she’s advertising various things in the newspapers. But then she is also seeking out other places to do her work, whether it’s the yearbook photos, taking pictures of the faculty, or taking pictures that get published in the newspaper of people’s gardens, and that kind of thing.

By 1940 Margaret has successfully been running the studio now for twenty some years.

She’s still a photographer in the 1940 census; she’s now sixty years old, her mother, Nellie, has come to live with her and her aunt, Elizabeth, Nellie’s youngest sister, has come to live with them as well.

So things continue right along until May of 1942, the last time an advertisement for the Margaret DeM. Brown studio appears in that Poughkeepsie newspaper.

Looking further afield to start to understand what happened [next], we discover that Nellie Brown unfortunately passes away in September of 1942, but she actually dies in Springfield, Massachusetts, not in Poughkeepsie NY. Her obituary specifically mentions that she’s only been in Springfield for a few months, having just moved there from Poughkeepsie.

It would appear that what happened was Nellie started to get sick, and Margaret makes a decision to move with Nellie to Springfield, Massachusetts, because Springfield is where Margaret’s youngest sister, Mary, has moved to, having married a man named Ballard Sexton some years before.

As it turned out, 1942 contains a series of upheavals for Margaret Brown.

First, her mother dies.

Her sister’s husband, Ballard, registers for the draft, and there’s a fear that he can be called up at any time, even though he’s already forty-seven years old.

And then her friend Helen, back in Poughkeepsie, well she get sick at the end of 1942 and passes away unexpectedly at the beginning of 1943.

Margaret makes a decision to settle in Springfield instead of going back to Poughkeepsie. As far as I can tell she doesn’t actually reestablish a photography career in Springfield, rather settling there as a retired woman, living with her sister and brother-in-law, and then after Ballard dies in 1946, living just with her sister.

Margaret dies in Springfield, Massachusetts after a brief illness in 1959. She’s buried with her brother-in-law, Ballard, and ultimately with her sister Mary, Ballard’s wife.

Mary lives until 1973.

Before that, in 1961 Mary donates a number of pictorialist photos to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Now these pictorialist photos are not done by her sister, but by her sister’s contemporaries in the Pictorialism arena back around 1916-1920. Clearly pictures that Margaret had had, works of friends of hers that Mary has inherited and now is donating to the Museum of Modern Art in her sister’s memory.

Mary’s relationship to the photography and to pictorialism is kind of interesting to speculate. I believe that she is the model for one Margaret’s early pictorialist works, that “Portrait of MCB”.

There’s no mention of Mary actually doing photography in anything that I’ve discovered, except for the fact that she actually became a teacher at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Now, the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn was the place that Gertrude Käsebier had studied art. So I’ve got to wonder if there is some influence from Käsebier to get Mary to go teach at the Pratt Institute.

Mary is ultimately a teacher in the Springfield school system, but it is never mentioned what exactly she taught, so I don’t know for sure that she did anything related to art.

But is intriguing with these donations to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, because some of the donations are actually tied to donations by Gertrude Käsebier’s granddaughter. Trying to understand the relationship between the families is one of the areas I’m continuing to pursue as I try to uncover as many traces as I can of the life and career of Miss Margaret DeMotte Brown.

To see the photo that Margaret did of FDR, the one that’s at the Library of Congress, and some other materials relating to Margaret, go to my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers.net.

If you have any questions, or just want to drop me a line, send an email to podcast “at” p3photographers.net.

That’s it for today. Thanks for stopping by!

Until next time, I’m Lee, and this is Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

3 thoughts on “03 Finding Miss DeM. Brown”

Comments are closed.