Notes

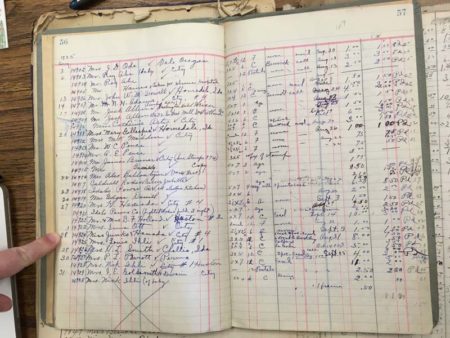

Here’s what a sheet from the ledger books look like from the Snodgrass Picture Shop (this page is from the ledge for 1935):

The majority of the negatives indicated in these ledges that are for portraits of people are of that format, with the two different poses on a single negative. There’s a notation in the ledger for how many prints were made; there’s usually also a mark on the negative itself as to whether or not a particular pose was printed. Here’s a digital “contact print” I made on the computer of that negative; the Snodgrasses would have produced prints separately of each pose, not a print with the two photos like this one:

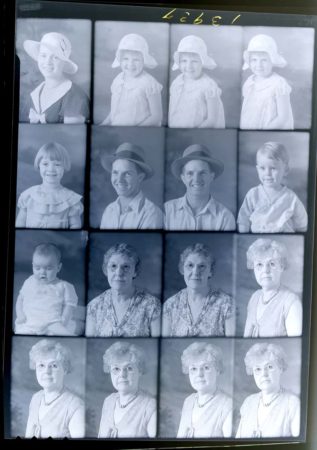

Stamp photos were produced from negative sheets that had grids of multiple exposures, sometimes 9×9, sometimes 4×4. Mary and Margaret would sometimes seemingly take photos of themselves to fill up the “grids”. Here’s a grid that has Margaret (flowered dress) and Mary in the last 7 photos on the card. Ironically, this sheet has one of the few photos of a baby that we have found in the archive; the baby is just before Margaret, and Mary is after that. Perhaps that’s why they both look a little tired in their photos… 😉

Jan Boles of the College of Idaho Robert E. Smylie Archives has made some contact prints to show some examples of the wide range of photo subjects taken by the Snodgrass Picture Shop (all photos in the slideshow below are courtesy the Snodrass-Stanton Collection, Robert E. Smylie Archives, COI). Here are a few examples:

I’ll leave you today with two views of Mary Snodgrass. As I mentioned in the episode, when Mary dies in 1969, her obituary in the Caldwell Times newspaper includes a photo of her:

But of the many photos we’ve found of Mary, I think this one is my favorite:

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- Ancestry.com (census records, city directories, and more; paid account required – Visit

- College of Idaho Robert E. Smylie Archives, Caldwell, Idaho – Visit

- Family Search website has U.S. Federal Census and more; free account required – Visit

- Geneologybank.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Marion County Historical Society, Knoxville, Iowa – Visit

- Newspapers.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

- Newspaperarchives.com has a selection of digitized newspapers from the United States; paid account required – Visit

The following links aren’t directly related to the Snodgrass family in any way, really, but … there was close connection between the two towns where Mary and Lucian ran their studios, Knoxville, Iowa and Caldwell, Idaho. As I mentioned in the podcast, the Steunenberg family was very prominent in both towns. Frank Steunenberg was governor of Idaho until 1901, and was assassinated while at home in Caldwell in 1905. The subsequent trial is sometimes referred to as the “trial of the century” in Idaho. Here are couple of links related to that trial:

- Assassination: Idaho’s Trial of the Century -website about the trial – Visit

- Assassination: Idaho’s Trial of the Century – video dramatization (produced by Idaho PBS) – Watch

- Big Trouble: A Murder in a Small Western Town Sets Off a Struggle for the Soul of America, book by J. Anthony Lukas – Buy

- Monograph, A Public Silence Broken: The Murderer Harry Orchard’s Forgotten Family – pamphlet by Jan Boles, COI Archivist – Info

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

Support for this project is provided by listeners like you. Visit my website at p3photographers “dot” net for ideas on how you, too, can become a supporter of the project.

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols & Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host, Lee McIntyre.

In today’s episode we’ll see how silver can become gold, and how forgotten books can be the keys to unlocking the story of two sisters and the photography studio they ran together in the early 20th century. All that and more in today’s Part 2 as we continue the story of the Snodgrass Picture Shop.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers “dot” net.

******

Serendipity — when something wonderful can unexpectedly happen.

Now, it’s hard to see at first how something wonderful can come out of having a broken arm.

But as it turns out, that’s exactly what happened with some of the negatives from the Snodgrass Picture Shop.

It was 2009, and Walter and Alice Braun had just closed their photography studio in Caldwell, Idaho.

They’d been running that studio for over 60 years. Walter, who was the primary photographer, had decided to retire at the age of 90.

Alice, his wife, had just broken her arm, and their daughter decided to come to help out while her mother was recovering.

While wandering in the basement one day, the daughter ran across a bunch of boxes that were all packaged up and labelled “ready to go to melt down.”

It turned out that inside those boxes were 500 pounds of silver nitrate negatives, photo negatives that could be melted down and the silver extracted for money.

That was what it was intended to happen with those boxes.

But the daughter thought that maybe somebody would be interested in the photos themselves.

These were negatives that covered 16000 images – the output of 80 years of photographic studios there in Caldwell, not only the Braun studio, but also the Stanton and the Snodgress studios before that.

So the daughter coordinated with someone who coordinated with some archives and the next thing you know, the Braun studio archives, i.e. the negatives from the Braun studio, well those got donated to the Idaho state archives.

But the rest of the negatives — from the Snodgrass and Stanton studios — those negatives wound up getting donated to the College of Idaho right there in Caldwell.

As if that wasn’t fortuitous enough, a couple of years later the archive received another call that suddenly, in the back of an old sock drawer, a bunch of ledgers were discovered — ledgers that actually last list all those negatives were!

This is just pure gold now.

We’ve got the negatives from the studios and the ledger books that explain what the negatives actually are.

The last bit of serendipity that comes into this is how I wound up discovering this archive at the College of Idaho.

My husband, Chris, and I had been researching early women photographers for this project, and we’d run across the name of Mary Snodgrass one day.

We discovered that she and her sisters all ran the studio there in Caldwell, Idaho.

This was a case where we’d run across the names, but we hadn’t run across any photos by them.

But then one day, when looking on the Internet, we ran across an article that had been written by the archivist at the College of Idaho, a man named Jan Boles.

The article, which was about the founder of the College of Idaho, a man named Dr. William Boone, was illustrated with a photo of Dr. Boone that had been taken by the Snodgrass Studio.

So, I contact Jan and ask if I could get a copy of that picture for my project…. and also, did he happen to have any other photos around by the Snodgrass studio?

You can imagine my surprise when Jan writes back that not only does he have more more photo – he actually has boxes and boxes and boxes of negatives … plus those ledger books from the Snodgress studio.

I mean, the Snodgress-Stanton collection at the College of Idaho is extraordinary.

It’s a collection of the everyday output of an artisan photography studio in the early 20th century.

The collection contains over 10,000 negatives, along with some original prints.

And, of course, those ledger books that document the photographs that are in those negatives.

The Snodgrass-Stanton collection contains the output of both the Snodgress Picture Shop from 1918-1938, and then also some negatives from the Stanton Studio that was the successor to the Snodgress Picture Shop.

But the bulk of the collection is the negatives from the Snodgrass Picture Shop between 1918-1938.

Now, Mary and Margaret Snodgrass, and Jesse Snodgrass when she was still there, well, all of the Snodgrass siblings had very close professional and social ties to both the town of Caldwell and also to the College of Idaho.

In addition to the usual types of portraits of people in town, the Snodgrass studio took pictures of local businesses and events in town, and also the student pictures for the College of Idaho yearbooks and the high school yearbooks in neighboring towns.

Interestingly enough, at least in the period 1919 to 1939, one of the things that the Snodgress studio does not seem to have done — at least not much — is take pictures of babies.

Baby photos seem to have been the staple subject matter of artisan photographers in the 19th century, and certainly continuing today, so it’s interesting to note that for the Snodgress studio, well, that just wasn’t one of their specialties.

Now the negatives are all labeled with numbers on them.

Also, there are some notations for the names of the people who ordered the photos, that’s actually noted on the negative as well.

All of that corresponds to the information in the ledger books, so you can easily look up for any given negative who it was that’s in the picture, who ordered it, how many copies were paid for, and how much was actually paid for them.

We can find all kinds of things in these photos.

I mean, there are pictures of ordinary people as well as prominent people, like Dr. Boone; it was, of course, a picture of Dr. Boone that led me to the archive to begin with.

In addition to the regular school pictures and the regular portraits of people, there are also something called “stamp photos,” which are small passport-size photos of people.

This is a style of photo that the studio decided to invest in at some point.

It required different equipment, and so it’s interesting to note that in the archive we find these stamp photo sheets, which are negatives that are they’re divided into grids, e.g. 3 x 3.

Now, finding this collection and getting access to work with it has been extraordinary because it provides new insight into how Mary and Margaret Snodgrass went about their business of running that studio.

We get a sense of how they were doing year over year; what kinds of supplies they were buying, what kinds of cameras and equipment they needed, what kinds of photos were particularly popular, etc.

When those stamp photos come into vogue, for example, it appears from the ledgers that they would set aside a particular time during the week to do that kind of photo.

They would actually have to change the equipment [to take the stamp photos] so that makes a lot of sense.

And also some of the pictures that exist of Mary and Margaret are when they’re filling in the [stamp] card, as it were.

[As I said] stamp photos are done on a negative where you’d have, like, a 3×3 grid.

So, if they had their last card of the day and there was space on the last negative, it looks like Mary and Margaret might have just taken a couple pictures of themselves.

And that’s kind of fun to find in the archive.

Now in addition to the Snodgrass-Stanton information that’s in the College of Idaho archive, there other materials that actually fill in some of the gaps about Mary and Margaret’s life there in Caldwell.

As I mentioned last time, Dr. William Boone, who was the founder of the College of Idaho, was an avid photographer.

He was an amateur, but he did a lot with photography and had different kinds of equipment.

[He did photography activities with Mary], where they would go out do their photography shoots on a Saturday afternoon occasionally.

And it’s also fun to discover, though, that Dr. Boone was an avid diary keeper.

He kept a daily log of his activities for many, many years.

Several years ago, Jan Boles, the archivist at the College of Idaho, arranged for someone to transcribed the original diary, and so that’s really accessible now to search .

And so, when we got to the College of Idaho the first time, we actually dove into that transcription to see if we could find any mention of Mary or Margaret Snodgrass.

It’s fun to see Dr. Boone’s notes to himself, e.g. when he recorded the days that he went to get his picture taken.

And that’s actually made it easy to track down some of the pictures of him in this archive.

Again, 10,000 images are a lot to sort through.

Anotherthings from [Dr. Boone’s] diary also solved a little bit of a puzzle that my husband, Chris, and I had run across when we were first researching Mary and Margaret Snodgrass.

In the census record from 1930 Margaret Snodgrass is listed, as she has been, as being “single”, but in 1940 what was puzzling is that it said she was “divorced”.

Now in 1930 she was almost 60, and it was surprising to think that she might have gotten married after that [for the first time].

But sometimes in the census records we do see notational errors, and so we had just brushed it off as OK, maybe it was just a mistake, maybe it didn’t really mean she was divorced.

However, Dr. Boone’s diary, there is an intriguing entry on May 18, 1932:

Great excitement in town. Dr Elmer Dutton and wife, nee Miss Margaret Snodgrass married 11 days now seek divorce. Folks wonder?

So, Margaret Snodgrass marries at the age of 59 to a man named Elmer Dutton, who was a local, very popular — and prominent — doctor in town.

But obviously the marriage doesn’t last long – only eleven days!

Unfortunately Dr. Boone is rather mum on the subject in his diary, so I can’t tell you anymore about what happened.

After the divorce, Margaret Snodgrass goes back to using “Snodgrass”; she’s no longer “Dutton,” which is why we had no clue until we saw Dr. Boone’s diary [that she’d actually gotten married and divorced in the 1930s].

You just never know what kind of information you’ll find – or where it’s going to come from – when you’re looking into the lives of these early women photographers.

Now Mary and Margaret Snodgrass run that studio, as I said, until 1939 when they retire.

They sell their studio to a man named Stanton, and luckily he kept all of their negatives and their ledger books.

So when he sells his studio to Braun in 1947, Braun inherits all that material.

And luckily for us, he kept it as well.

And fortunately for us, the negatives were recovered before they were sent off to be melted down.

After Mary and Margaret Snodgrass retired, they continue to live in Caldwell.

We talked to the local historian in town, Chuck Randolph, who recalls being a boy in the 1950s, delivering newspapers to the two Snodgrass ladies.

But from his perspective [as a kid] in the 1950s, they were just elderly ladies; he didn’t have any idea they’d ever been photographers.

But of course, by the 1950s, it had been a long time since they’d run the Snodgrass Picture Shop.

Well, Margaret dies first, in 1954; Mary lives until 1969.

I always hesitate to say it’s “fun” to find the obituaries, but the obituary of Mary Snodgrass actually has a picture of her that’s included in the obituary in the Caldwell Times [newspaper].

I’ll include some of the pictures that I mentioned in the episode notes for today’s episode, so you can actually see Mary and Margaret, and also some of the types of pictures that they took there in the Snodgress Picture Shop in the early 20th century.

Now there’s a lot more that can be learned from those ledgers and this collection.

But unfortunately I haven’t had a lot of time to sit down and really analyze it properly.

So I’ll just have to promise to bring you that in a future episode.

Before I leave Caldwell today, though, I’d like to give a special thanks to Jan Boles, the archivist at the College of Idaho.

Jan has been so helpful and so generous with his time and understanding of the materials and helping us figure out what’s there and how we can utilize it for research on the Snodgrass family.

Jan’s experience as a professional photographer running a professional studio for awhile has really also been invaluable, because he’s been able to explain a lot of the materials and what was involved in working with them, the technologies, the papers, and the film, and the types of things that Mary and Margaret were doing there with their studio in the 1920 and 1930s.

I also want to give a special thank you to some of the assistants that Jan has had, including a woman named Bess Steunenberg

She who wasn’t actually Jan’s assistant, but she did assist in transcribing Dr. Boone’s diary, which is [part of ] what makes it so easy to search it these days, having that transcription available on the computer .

She did that transcription of Dr. Boone’s handwriting to a typewritten version, and then Jan has actually put that on the computer, so that’s been great to have as a resource.

I also want to give a big thank you to a woman named Emma who worked with Jan when he first got that collection years ago.

Emma managed to sort and organize all of those 10,000 negatives, putting them in archival sleeves for protection, and making a log of all of the negative numbers and the notes on the negatives.

That log is digital, and so that, combined with the [original] ledger books, have made it really easy to sort out what’s actually in those photos.

I would also like to thank David Douglass, as well as other faculty and staff at the College of Idaho who have all been very supportive as we’ve worked with this Snodgrass-Stanton collection.

And I want to give a special thank you to Chuck Randolph, the historian there in Caldwell, who has generously donated time and materials to help give us an understanding of life in Caldwell.

But as I said, there is a lot more that we can learn from those ledgers and from this collection, and I’ll be bringing you that in a future episode.

And that reminds me …

Today is actually the last episode in Season 2 here on the podcast.

It’s hard to believe, but it’s been a year since I launched Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.

As I look forward to bringing you Season 3, there’s going to be a couple of little tweaks – few surprises that I have in store, because I really want to bring you more of these women’s stories.

My husband, Chris, and I have been collecting this information for almost two years, and we have over 600 women that we’ve uncovered to date.

At the current rate [of 2 episodes per month] this will take us decades to get through! 😉

So starting with Season 3, I’m going to start offering a few other things, to bring you some more of the stories more quickly.

Which also reminds me: I want to give a special thank you to my husband, Chris.

He always refers to himself as “just” my research assistant, but he’s really so much more.

He’s doing some of the research as well, and moreover he’s doing a lot of the stuff behind the scenes on the computer, making little tools and making sure that all of the material that we’re gathering is properly organized so we have access to it as I bring you these stories.

So I really want to thank Chris for all of his ongoing help on this project.

And, of course, I want to thank all the listeners like you.

Without your support none of this would’ve been possible either.

Thank you for all of the messages, and the donations that have helped keep the project running over the past year.

I hope you’ll join me as we move forward into Season 3.

As always, information about all the materials mentioned on today’s episode will be available on the website, at p3photographers.net.

That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers “dot” net.

Also, if you have any questions, or want to just drop me a line, send an email to podcast “at” p3photographers.net.

Plus, remember you can always follow me on Facebook, at facebook.com/p3photographers.

I’m really excited as we move into Season 3.

I hope that you will continue to join me as I bring you this exciting world of early women artisan photographers!

So until then, I’m Lee, and this is Photographs, Pistols & Parasols.