Notes

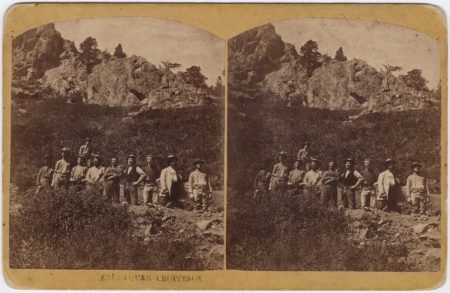

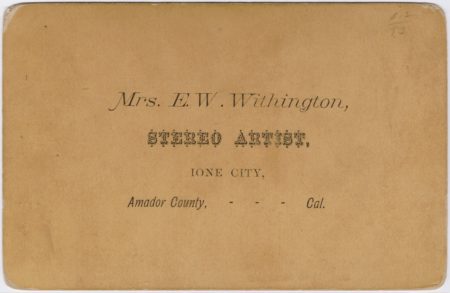

Not only did Elizabeth Withington do landscape photographs, she did stereocard versions of them, too, for viewing the images as 3D using a steroscope.

She also did standard portraits and studio work; check out some examples of those over on my Pinterest board for this episode.

The late Peter Palmquist, a great photo historian, did some pioneering work tracking down information about Elizabeth Withington. I’ve included some links below to some of his writings about her, as well as a transcript he put online that has the complete text of Withington’s 1876 article, “How a Woman Makes Landscape Photos.”

Palmquist also discovered that in addition to her photography, Elizabeth Withington had quite an interesting back story about the trek she made to join her husband in California in 1857:

In 1852 Eliza Withington traveled overland from St. Joseph, Missouri, to join her husband, George Withington (1821-1900), who was operating a ranch in Amador County, California. She was accompanied on the trip by the oldest of her two daughters. The hardships of the crossing were chronicled in the journal of a fellow migrant, Mary Stewart Bailey (see Jeanne Hamilton Watson, To the Land of Gold and Wickedness: The 1848-59 Diary of Lorrena L. Hayes). Shortly before 1857 Eliza Withington returned to New York to learn photography and visited the famous Matthew Brady gallery. — P. Palmquist, https://www.cliohistory.org/exhibits/palmquist/withington/

Palmquist also managed to track down a photo of Elizabeth Withington, taken by the photography studio of Bradley and Rulofson:

It’s not a selfie taken by the photographer herself, but it is the next best thing! Of course, I am somewhat curious to know if there’s any significance to the book she’s holding (Tales of Naval Adventure) — or the fact that she’s holding it upside down. A bit of an intriguing mystery I have no answer for at the moment.

Anyway, one final note: As I mention in the episode, Elizabeth Withington’s instructions to a woman photographer on the importance of carrying “a strong black-linen, cane-handle parasol” inspired part of the title of this podcast.

The title of this episode, though, was inspired by some of the lyrics of a rather obscure Jerry Herman song from the musical Dear World. The song, called A Sensible Woman, was cut from the original production, but could have been sung to describing Elizabeth Withington’s masterfully unconventional approach to doing landscape photography:

.. A sensible woman … when faced with a problem …

… with her eye on its target, her parasol brandished,

with wisdom, and wit, and élan —

a sensible woman goes on! —Jerry Herman

Lifeline

Recommended Links

- “How a Woman Makes Landscape Photos” by Elizabeth Withington, 1876. – Read

- Short Bio of Elizabeth Withington by Peter Palmquist – Read

- The Beineke Library website has a few digital images from the Peter Palmquist Collection of Women Photographers – View

- Palmquist, Peter E. (editor). Camera Fiends & Kodak Girls: Writings by and About Women Photographers 1840-1930 – Buy

- Palmquist, Peter E., and Gia Musso. Women Photographers: A Selection of Images from the Women ln Photography International Archive 1850-1997. Kneeland, California: Iaqua Press, 1997 – Buy

- Palmquist, Peter E.. Shadowcatchers: A Directory of Women ln California Photography Before 1901. Arcata, California – Buy

- To the Land of Gold and Wickedness: The 1848-59 Diary of Lorrena L. Hayes, Jeanne Hamilton Watson (editor) – Buy

Transcript

You’re listening to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols, the podcast where we celebrate early women artisan photographers.

I’m your host, Lee McIntyre.

Today I want to tell you about Elizabeth Withington, a nineteen century artisan photographer who was well-known among her peers for outstanding photography, as well as her skill at fashioning practical photography tools out of 19th century ladies fashions.

For more information about any of the women discussed in today’s episode, visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers dot net.

Elizabeth Withington was born in 1825, and she opened her first studio in 1857.

She did studio portraits, but by the 1870s she was also becoming noticed for her landscape photos.

The photos themselves were quite good, but the other thing that was attracting attention were rumors about how she was taking her landscape photos.

The technology she was using was called “wet plate photography”, and that was popular for both studio photos as well as for taking landscape photos.

But it was a bit cumbersome, because you had to work with the glass plate right after it was coated with liquid, before the plate got dry.

It was, after all, called wet plate photography.

Typically you had no more than ten minutes before the plate would start to dry.

Once the photo was exposed, within those ten minutes, you then had to get that plate into a developing solution right away, or else the photo would be ruined.

Both the coating of the plate as well as the developing of the plate, well, those things needs to be done in complete darkness.

So when you look a history books for this period, you’ll see mention of the civil war photographers.

Now they were using this wet plate photography.

And all of the stories about the civil war photographers talk about how, when they took their battlefield photos, off on the side of the battlefield would be their darkroom wagon, parked, ready for them to dash into in order to develop the image.

Because typically photographers doing wet plate photography would have their own darkroom wagon — that was how you had to do it because you needed a darkroom.

But Elizabeth Withington, well, she was not your typical photographer.

She’s sort of atypically would travel by public transportation, like stagecoach, or maybe by hitching a ride on the fruit wagon.

Which meant that she would travel without a portable darkroom [wagon].

So people wondered, how could she possibly do wet plate photography?

I mean, you needed a darkroom.

But Elizabeth Whittington was clever.

First, she considered the problem of the wet plates.

Conventional thinking said you couldn’t possibly coat the plates ahead of time, because they would dry out too fast.

But she discovered that by carefully wrapping the coated plates in a wet towel, she could extend the limit to not just 10 minutes but more like a 180 minutes —or three hours worth of time — for her to coat them at home and then use them in the field.

So, the first problem of needing a darkroom in the field solved by pre-coating the plates and keeping them wet in that towel.

But then, once she got to her sun-drenched meadow and she took her photo, how in the world was she going to be able to develop the image without having a darkroom at hand?

Once again, an unconventional solution was at hand.

Because Elizabeth Whittington got the idea of taking a dark petticoat, and then turning it into a wearable darkroom petticoat tent.

She designed it so she could slip it over her head, down to her waist, and then in total darkness be able to apply the developer solution to stabilize the exposed image, so that she could then take it back to her darkroom for final processing.

This is very creative, and it allowed her to deal quickly with any of the photos that she took out in the field, particularly if she had just stepped off the stagecoach to take the photo.

She later wrote that she could do it so quickly that the stagecoach driver would not have to wait extra for her to process her photo.

She became famous, as I said, for her photos as well as for her techniques.

In 1876 she was persuaded to write down the details of her techniques in an article that was called “How a woman makes landscape photographs.”

In that article she describes how she uses the wet towel and the petticoat darkroom tent as photographers tools for doing landscape photos.

I mentioned a moment ago, what happens if she’s standing on the sunlit field when she’s taken the photo and she needs to develop it?

But she also had mentioned in that article of what she would do when there is too much sunlight on her camera.

Because she writes about the importance to a woman photographer of a parasol.

Now, parasols were common for women to carry in those days, but she says that a woman photographer needs a strong black linen, cane-handle parasol.

That’s a necessary photographers tool, not just for the shade for the photographer, but also for improvising a lens shade when you’re out in that sun drenched field, and there’s just too much light on your lens.

Elizabeth Withington also points out that a parasol can be good for steadying yourself as you’re walking across rough terrain to get to your photo-op.

In addition, she comments that it would be useful if you wanted to slide down into a ravine to assess another opportunity for a photo.

That’s not exactly a standard picture you get when you hear about Victorian ladies with parasols, but that was Elizabeth Withington’s advice to women photographers in the Victorian age.

Unfortunately, Elizabeth Withington died from cancer at the age of only fifty-two in 1877, just one year after her article was published.

She had worked as a professional photographer for twenty years, and a few examples of not only her landscape photos but also her studio portraits have survived to the 21st century.

But her legacy is not just in those photos, but also in that wonderful 1876 article which explains those unconventional tips about using a petticoat and a parasol as photographers tools.

I’ll include a link to a copy of it on my website, so you can read all about her techniques and advice on doing photography in the field.

Of course, nowadays we don’t have to worry about the wet plates and the wet towel.

But Elizabeth Withington’s creativity, resourcefulness, and can-do spirit for solving problems posed by camera technology provide inspiration to photographers of any time period.

By the way … the title of this podcast is indeed a tribute, in part, to Elizabeth Withington and her instructions to women photographers everywhere on the practical uses of a sturdy black linen, cane-handled parasol.

For more information about any of the early women photographers profiled on the podcast, visit my website at p3photographers.net. That’s letter “p”, number “3”, photographers dot net.

Or, drop me a line at podcast “at” p3photographers.net.

That’s it for today. Thanks for stopping by!

Until next time, I’m Lee, and this is Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

1 thought on “08 A Sensible Woman”

Comments are closed.